Confluences: St. Louis & its Hinterlands

—core studio in the 2nd year of the MLA program

Washington University in St. Louis

Fall 2019

Teaching Assistant: Virginia Eckinger

Tianhao Xiang holding his atlas of research about nuclear energy, in his selected site on the Gateway Mall.

The Gateway Arch commemorates the role of St. Louis as a launching site for the settlement of the American West. For many, the monument no longer evokes Manifest Destiny, but conjures modern architectural ideals and feats of engineering in the 20th century. The 21st century redesign of the Gateway Arch National Park reconnected city to park and drew the indeterminate environment into the design. In this way, the St. Louis riverfront has long been a testing ground for architecture and landscape as representations of our history and aspirations.

While the Gateway Mall also points to Western Expansion, the City Beautiful movement drove the removal of the historic urban core for the construction of the string of parks. Ideas of aesthetic clarity, open space, and civic monumentality lay the groundwork. However, block-by-block, designers and stakeholders have shaped and reshaped the open space over time. The Mall recently has undergone multiple redesigns, and the character seems to be shifting away from openness, toward intensive greening and increased biodiversity. Again, landscapes represent history and aspirations.

If we extend our monumental axis, through Danforth campus, where does the imaginary line go? Would we draw up the Missouri River or a straight section across the continental divide and down to the Pacific Ocean? How many crude oil and natural gas pipelines would we cross? How many coal mines? Is our West-facing axis pointing to the fact that much of St. Louis’s infrastructure lies ‘out West?’

This second year Master of Landscape Architecture studio will trace infrastructural lines—from Downtown St. Louis to the hinterland and back. We will travel to Montana and Wyoming, to understand what connects St. Louis and the American West. Through drawings we will understand how infrastructure overlaps with ecology and how economy and politics impact landscapes. Beyond westward and upstream, we will look downstream to understand the whole watershed context; we will also look worldwide and try to disentangle a globalized network of resources and environments.

Students will tell an informed story about how St. Louis and the American West developed, how US infrastructure is changing, and what St. Louis might stand for in the future.

Finally the studio will return to the Gateway Mall and the Gateway Arch National Park in Downtown St. Louis—the studio site. Students will ground their research through the design of a dialectical landscape—one that fosters the exchange of ideas and invites opposing forces. The projects will visualize our history, especially the 20th century infrastructure on which we depend. We will use design to communicate changing priorities in the 21st century.

The landscapes and questions in this studio are monumental, so each student will study one infrastructure and each design project will take one clear position. The studio will employ large maps and valley sections to understand our continental context. Experimental drawings and models will conflate our site with the hinterland and serve as generative tools. Then students will clarify and refine their site designs on or adjacent to the Gateway Mall and Gateway Arch National Park.

Confluences Mapping

Students developed a unique lens through which to read the relationship between St. Louis and the American West, by first studying an infrastructure over time and across the continent.

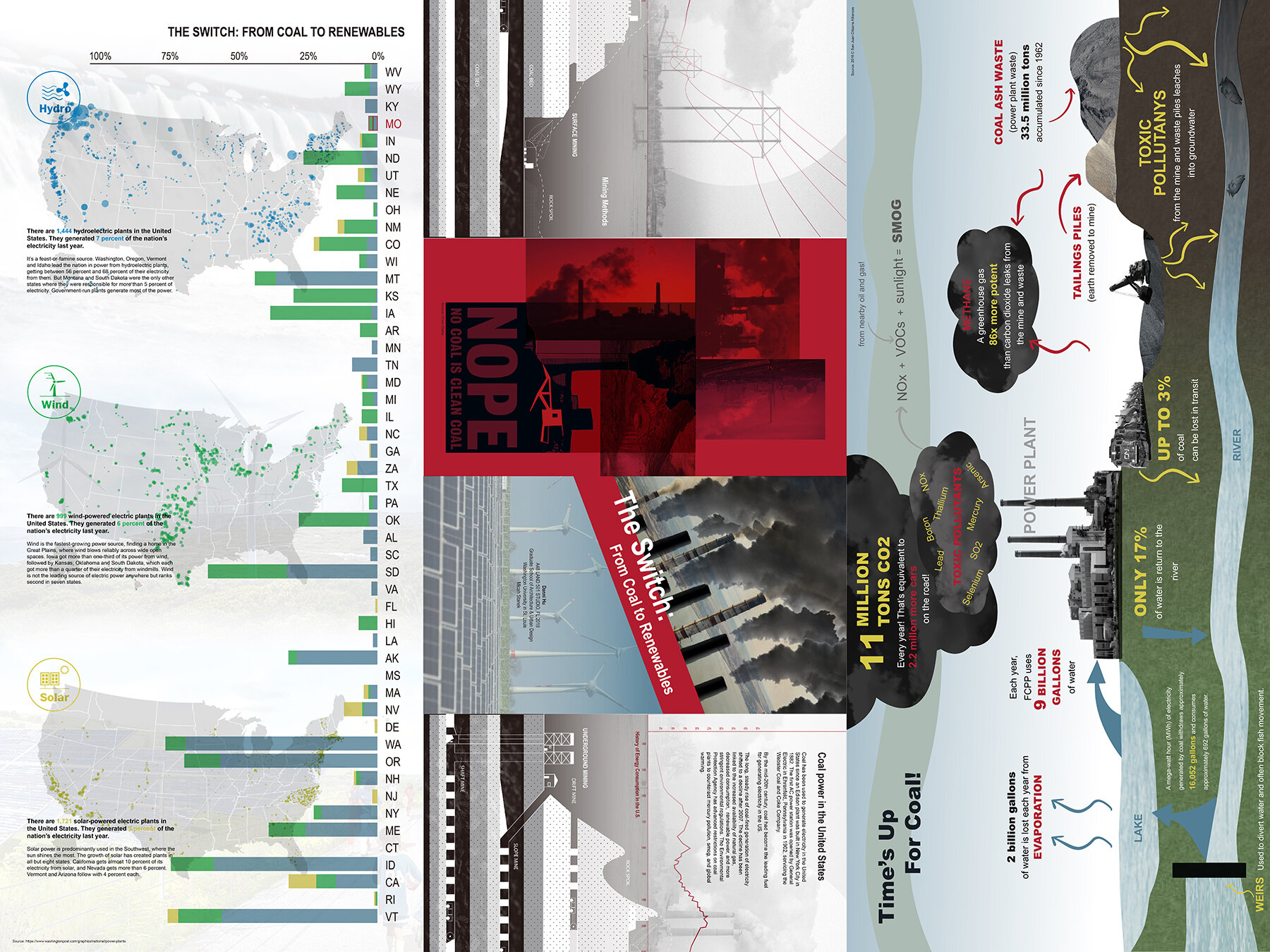

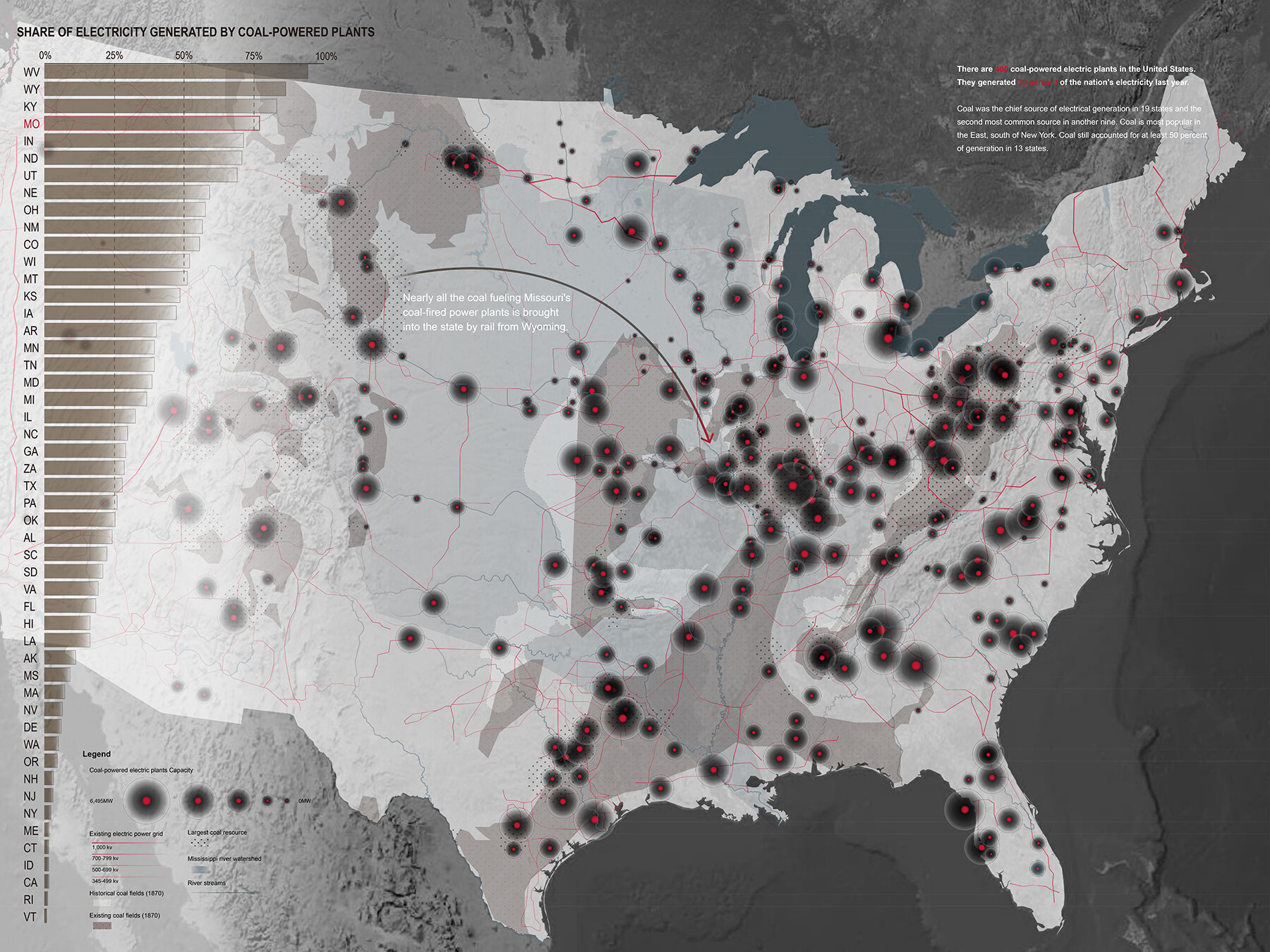

Next students individually collected GIS data, historical maps, and other sources of information to create a synthesized “Confluences Mapping.” The folded, two-sided poster (a.k.a. atlas) depicting how the student’s infrastructure intermingles with other critical infrastructures and ecological systems. The aim was to fill these atlases with rich information, but also make these speak about the students’ own ideas about their infrastructure—its past and where this narrative might go in the future.

We reviewed these research documents, brought them on our studio trip, and then finally employed them as wayfinding as the students homed in on sites and propositions in the City of St. Louis.

Danni Hu

The Studio Trip

All 12 students and I took a trip Montana and Wyoming. We flew to Missoula, Montana and then toured in a caravan, back and forth over the continental divide. We visited:

Milltown State Park Confluence Area, a superfund site, where a dam that held back toxic effluent from the largest metal operation in the US. Now a plume of arsenic is held in place underground and the Clark Fork River can freely mix with the Blackfoot River.

Lubrecht Experimental Forest, a forestry field station owned by the University of Montana, operated for profit and used for education, research, and recreation.

Missouri Headwaters State Park, where three rivers combine and are renamed Missouri. The Lewis and Clark expedition came through this site in search of navigable rivers near to mountain passes, to cross the continental divide. These US explorations furthered the Manifest Destiny nation-building project.

Canyon Ferry Dam and Reservoir, which is the first dam on the Missouri River. We stopped at one of the many campsites and occupied the ever-changing edge of this human-made body of water. Because we were not able to stop and see the dam on foot, we drove over slowly to soak in this monumental infrastructure.

Yellowstone National Park, where we visited some of the volcanic features, taking note about how the site design and interpretative materials guide visitors to behave, observe, and perhaps learn. We walked many meters of boardwalks and stairs, but also hiked along the canyon, drove many kilometers, and stopped for observe wildlife or people observing wildlife. We also camped one night in the park.

On the last day, we opted to skip a planned visit to the World Museum of Mining in Butte, Montana. We had already learn so much about the legacy of Butte mining and its famous tailings. Instead, we caravanned around Missoula, visiting a landfill, a water treatment facility, a nutrient reclamation project (which is also a poplar farm for wood pulp). We encountered a climate change demonstration in the middle of town. We followed the higher streets to the riverfront, taking cues from utility poles and location marks, to discover how infrastructure comes into the city, goes underground, enters buildings, and flows down to the river.

While on the trip, the students were tasked to find evidence of their infrastructure, on the road or around our site visits. Some of their infrastructures are invisible, so students were thinking about how to ground truth something known from their research, find materials tied to their infrastructure, or conflate their research with like landscape qualities. By working this way, we were looking for signs, visible infrastructure, and thinking about significance of sites that cannot be seen, but can be known through our mapping projects.

The Photo Essay (and the 2 Fictions)

Out of the many trip photos, the students selected a few to speak about what they found most interesting about their infrastructure research. By editing the series over the course of the semester, the students are using found landscape conditions to describe something about the legacy of their infrastructure.

Then, by adding fictions to the landscape photography, the students are responding to the past and current conditions. The fictions also begin to imagine landscape futures.

Photo essay and renderings by Xue Ying

Site Selection (on the Gateway Mall in St. Louis)

The students went through a mapping exercise to study site conditions and symbolic alignments in the Gateway Mall, which aligns with the Gateway Arch, the St. Louis riverfront, and which looks westward.

Danni Hu

The Projects

The students’ studied infrastructure at a continental scale and then designed parks along the Gateway Mall. The site designs aim to make these very public, accessible spaces speak about our relationships with distant landscapes, past and perhaps the future. The infrastructures studied were:

Coal and Cleaner Energy

Nuclear Energy

Wind Energy

Telecommunications

Natural Gas

Sewer

Water

Forestry

Limestone Mining

Coal Mining

Petroleum

Shipping

Danni Hu

Danni Hu

Danni Hu

Danni’s project visualizes the legacy of coal pollution and ash deposits around 3 nearby plants. The project maps the region in scale, but offers human scale through planting and markers as a further reminder of one of the environmental costs of our coal-burning legacy. The floodplain topography is made of recycled concrete and the coal pollution markers are made of recycled utility poles, become less necessary as energy becomes more generated onsite, as this project does through solar energy collection on a nearby facade.

Tianhao Xiang

Tianhao Xiang

Tianhao Xiang

Tianhao’s project visualizes how nuclear energy production heats environments around plants. Inside a underappreciated Richard Serra sculpture, “Twain,” the design reactivates the site with the addition of steam. In the winter, the steam warms the air around it allowing children and adults to play and loiter comfortably. Since the steam changes the microclimate on the site, Tianhao suggests that subtropical plants could grow here in advance of the shifting macroclimate produced by carbon emissions.

Lei Liu

Lei Liu

Lei Liu

The main gesture of Lei’s project shows how railways often cut and divide the urban fabric. While studying the history of shipping, Lei also became interested in how much carbon individuals in the United States emit for shipping alone. The stacked shipping containers visualize data, but also become a new infrastructure for swapping and recycling right in the middle of Downtown St. Louis.

Lei Liu