Locating Vitality in the post-trolley Delmar landscape

—core studio in the 2nd year of the MLA program

Washington University in St. Louis

Spring 2020

Teaching Assistant: Virginia Eckinger

Locating Vitality 2 crew right before spring break and the COVID-19 shutdown. Pictured (left to right) are Yixin Jiang, Nanqi Wang, Jingyang Shi, Zhiyi Feng, Bowen Chai, Heyue Liu, Jiaqi Guo, and Weicong Huang. Not pictured (out sick) are Sweeta Jura and Jonathan Myers.

The notion of ‘revitalization’ assumes that the vitality we desire in a neighborhood or city is ready-made. In order to recover an urban site—where something has been lost through a set of processes, leading to a decline—we attempt to import, design, and construct vitality.

What is meant by ‘vitality’ and how does it help developers make monetary value where before there was little to none? Who or what is valued in a mode of redevelopment that attempts to reproduce some codified form of vitality? Would we locate vitality in the tall-grass meadows of the north side of St. Louis—which emerged due to human absence and civic neglect? Can we see vitality in the self-organized public spaces that marginalized people create when they are excluded from gentrified enclaves?

Rather than serving outdated modes of redevelopment by commodifying vitality, this first-year landscape architecture studio will attempt to locate vitality on Delmar Boulevard, in the West End and Skinker-Debaliviere neighborhoods.

The Delmar Trolley’s run has ended, and this studio will begin by studying this newly disused transportation infrastructure. Students will draw the conditions left by the trolley design together with the infrastructural lines typically found in the urban streetscape. Utility location marks partially reveal the underground infrastructure, and these codes will train students to observe, research, and make many-layered maps. Beyond the infrastructural lines, the students will look for signs of human and nonhuman vitality and begin making their own interpretive marks.

The drawings and the digital line will then give way to forms of representation that better suit ecological perspectives. Their studies will grow and branch beyond the east-west Delmar streetscape, north and south into two neighborhoods, as well as over and under this many-layered infrastructural landscape.

Through these maps as well as three-dimensional vignettes, students will each develop their own understanding of urban vitality. Will the students find ecological corridors and patches by following their forms of vitality through alleys and greenways into vacant plots and parking lots? How might a dual lens—environmental and social—demonstrate how the students understand urban ecology?

The semester has two parts, with two integrated projects. The first is a an episodic streetscape design for the post-trolley Delmar Boulevard. The students will reimagine temporary or long-term use of the trolley infrastructure, while integrating their vitality concepts with this stretch of Delmar. The second project also stems out of the student’s vitality lens, and likewise branches beyond Delmar. The final scope of the studio is: a reimagined stretch of Delmar, a few proposed critical crosswalks, and a web of corridors and patches designed through the student’s unique ecological perspective.

Neighborhood Mapping

Jiaqi Guo’s mapping integrates rainwater, sewer, and freshwater infrastructure along Delmar Blvd (from Skinker Blvd to DeBaliviere Ave).

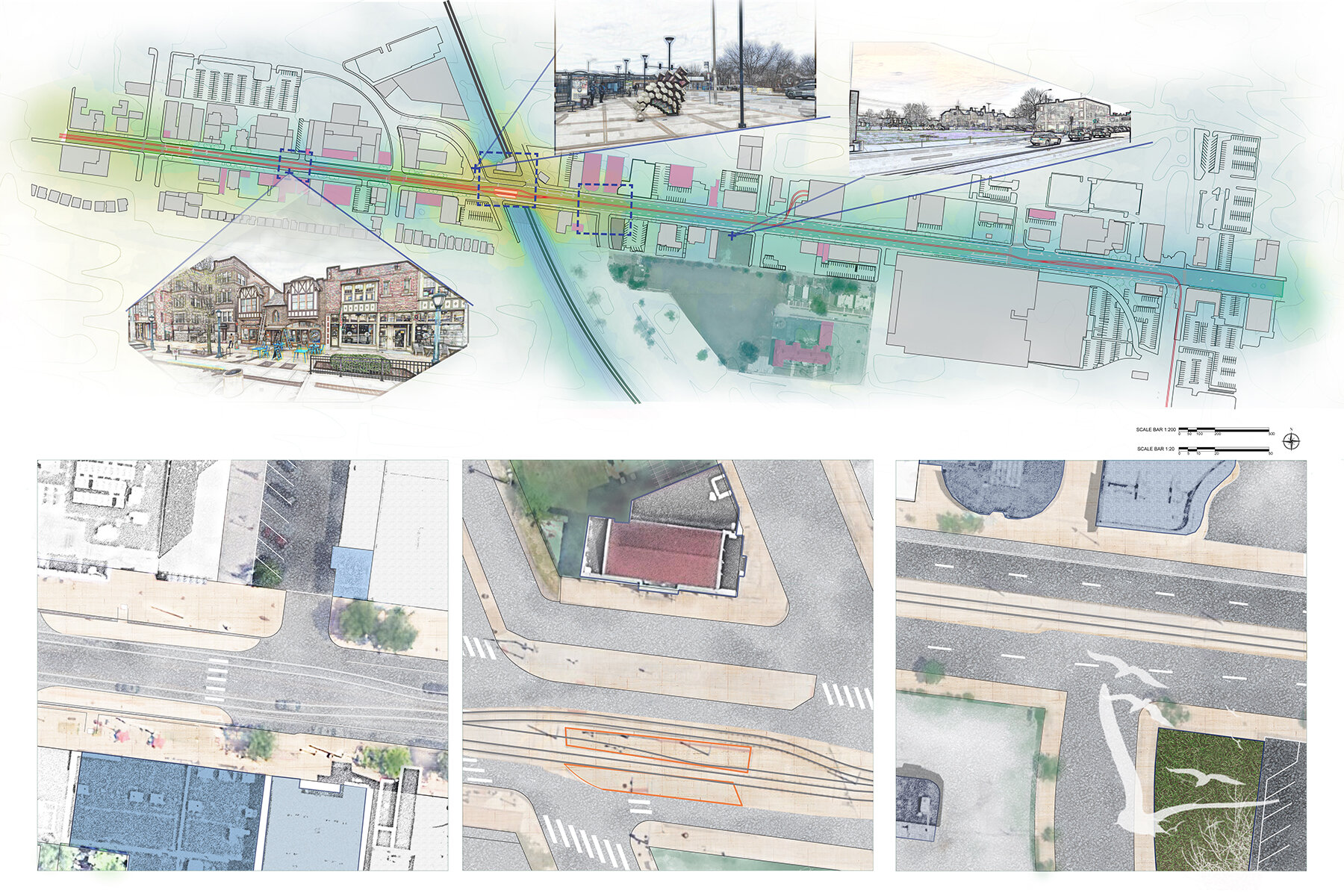

Heyue Liu’s mapping locates vitality in vacant spaces, including the disused trolley infrastructure. Above is the mapping and below are the plans showing existing conditions.

The mapping project asks students to draw a neighborhood according to what they learn from direct observation and tracing aerial maps, but what attempt to represent forms of vitality already present on site they see. Their vitality lenses will help them select sites and begin testing ideas on those sites. We discuss about how to communicate the way you see a site, and make the drawings accordingly.

As the students develop the map, they also make 3D vignettes to depict their phenomena-of-interest. See below.

3D Vignettes for Locating Vitality on Delmar Boulevard

Jiaqi Guo found the design of water infrastructure interesting, though they sometimes get in the way of streetscape design. Sometimes even new bioretentiion pools are not enough to deal with old, failing sewer infrastructure.

Heyue Liu found birds playing in a vacant lot, mothers walking along and across the street while holding hands with their kids, and emergent pools that reflect the sky but also beg kids to jump into them.

If/Then Series

Next, the students experimented with their ideas for supporting or multiplying their forms of vitality with small interventions or more intensive streetscape redesign.

Weicong Huang found architectural and infrastructural nooks on Delmar, which could multiply human and nonhuman vitality if they were open and flexible. The If/Then series then tested removing fences and making the material into social infrastructures. His series imagines various uses for the nooks, including social programs and also habitat for urban wildlife.

Jiaqi Guo’s If/Then series tested alternative uses of freshwater infrastructure, graywater recycling, and augmented raingardens.

Episodic Streetscape Design

For midterms, the students developed their streetscape ideas through 3 sections, 3 plans, and a few more 3D vignettes.

Weicong Huang’s sections, plans, and axonometric views highlight the conditions he is most interested in, which he planned to carry forward as he developed his work the rest of the semester.

Back to the Drawing Board

After the midterm review, the students decided what to keep and what to move forward in their project. The design process is repeated, but now the students also add a pocket park (a patch) to their episodic streetscape design (a corridor). The student’s vitality lenses begin broadening to design with their found phenomena in a larger ecological condition. The new neighborhood mapping is made to tell a more clear story about how the students see the site context, to seek and select their patch site, and to continue drawing to communicate the way they see their larger site.

This is also the point at which the COVID-19 stay-home order began, and the students finished the studio in a shortened half semester. The instructor delivered a lot of digital tools via recorded tutorials and we had one-on-one ‘desk-crit’ meetings on Zoom, where we drew together and continued touring the site through Google Streetview.

Heyue Liu kept base information from her initial neighborhood mapping, but further studied pedestrian movement, and synthesized her new mapping into a drawing that demonstrates a lack of play space in the neighborhood. Her final project was a site redesigned for supporting spontaneous, diverse play, also immersing neighborhood kids in reassembled native plant communities.

Weicong Huang retooled his initial neighborhood mapping to include his initial finding—architectural nook sites—as he developed his landscape nook ideas at Ruth Porter Park. The new patch also is part of the St. Vincent Greenway, further connecting his design to Forest Park and the Great Rivers Greenway web in St. Louis.

Site Study

After selecting their patch site, the students studied pedestrian flow, topography, water flow, seasonal and diurnal shadows, as well as other phenomena and materials found in their new sites. As the students iterate these drawings, we routinely discuss precision and clarity, but also experimentation and discovery. The final site studies hold information, but they also represent the students’ perspectives about the neighborhood and landscapes with which they are working.

Weicong Huang’s site study is presented as simple axonometric layers (slides above) and also integrated into one plan drawing of existing conditions and phenomena.

Site Design

For the ecological patch, the students developed their site designs in plan, section, and perspective. Many students made their first iterations in plan, this time, in order to take advantage of the site understanding from the (mostly) plan-based site studies. Sections and perspectives were required, but many students chose to make section-perspectives, in order to clearly communicate their spatial and material ideas in their final drawings.

Weicong Huang’s plan responds to a desire line in the site and uses gabion benches and architectural nooks for humans. At the same time, his paths and human nooks divide the site into environmental nooks that support nonhumans in many ways. Some of the paths raise up slightly to promote refuge and safe movement of nonhuman life as humans speed through the site running or cycling.

Flip through Weicong Huang’s 3 section perspectives (above) to see how his design supports and multiples social and environmental ecology. Weicong also considered maintenance, seasonality, and extreme storms, which might produce emergent pools and further produce more emergent habitat.

This course also collaborated in the last three weeks of the semester with Planting Design. While lecturer Eric Kobal taught about plant communities and block planting I introduced grasshopper basics and linked them to some advance publicly available scripts. The drawing below uses Joseph Claghorn’s script called “Vector Field with Drawn Vectors” from the website “Generative Landscapes” (generativelandscapes.wordpress.com). We used inputs from the mapping as attractor points to visualize flow of people and water. Then the highly variable script allowed the students to try to translate the mapping into a sense of drift in their bock planting designs.