An Environmental Learning Garden

2019

In development. A public landscape installation for combining ecology research with public engagement. In the mesocosm research garden is an experiment to test a native plant community for preadaptation for urban heat island effect and further climate change.

Research funded by Tyson Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis.

From left to right: Brooke Bulmash, Jacob Longmeyer, Alisa Blatter, and Doug Ladd—our botanist advisor and also the former Missouri Director of The Nature Conservancy. Doug was instrumental in preserving the Victoria Glades, a remnant ecosystem conserved in two tracts operated by The Nature Conservancy and the Missouri Department of Conservation.

St. Louis is full of vitality. In addition to its people, our commerce, transit, art, history, and tourism, St. Louis is similarly full of emerging ecosystems we hardly understand. As a team of designers invested in ecology, we propose a landscape installation to communicate, advocate, and discover new ecological ideas in the city.

This summer, our interdisciplinary collaborative—The Landscape Agents—has been in the woods at WashU’s Tyson Research Center, studying ecology and observing science experiments. We wanted to know what we could learn about the past of our environment, how ecological mechanisms drive our world today, and what we should expect for the future in the face of climate change. We have learned, through observation, how scientific research requires simplification of complex ecological interactions by only studying a subset of controllable factors. This led us to ask if these kinds of experiments could take place in an urban environment. The City of St. Louis has been a laboratory and scientists have studied our populations and tested the limits of our environments, but often without consent. To bend that curve, could scientific research share space, dialogue, or collaborate with a larger public? Could we all engage, define, and co-create urban ecology?

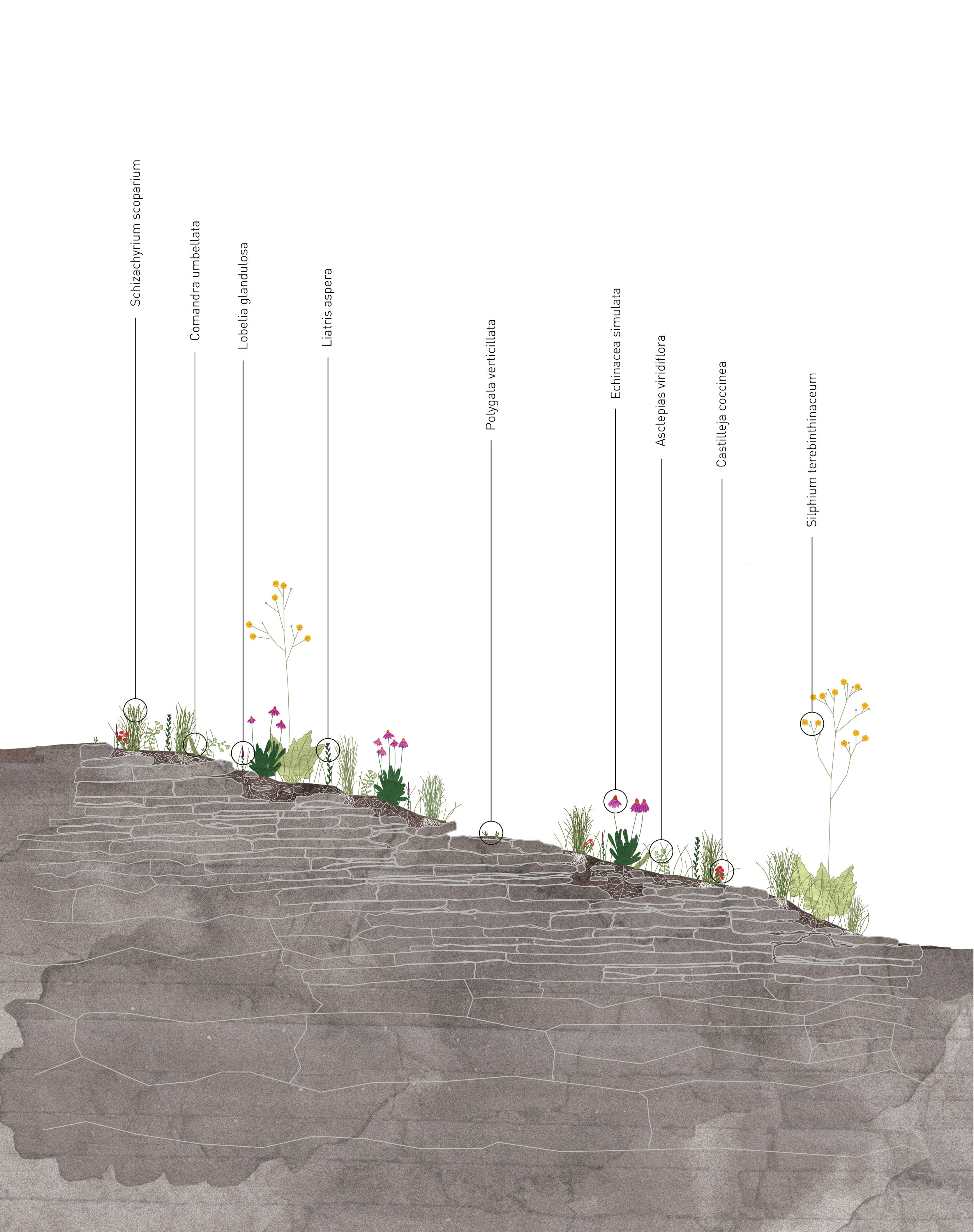

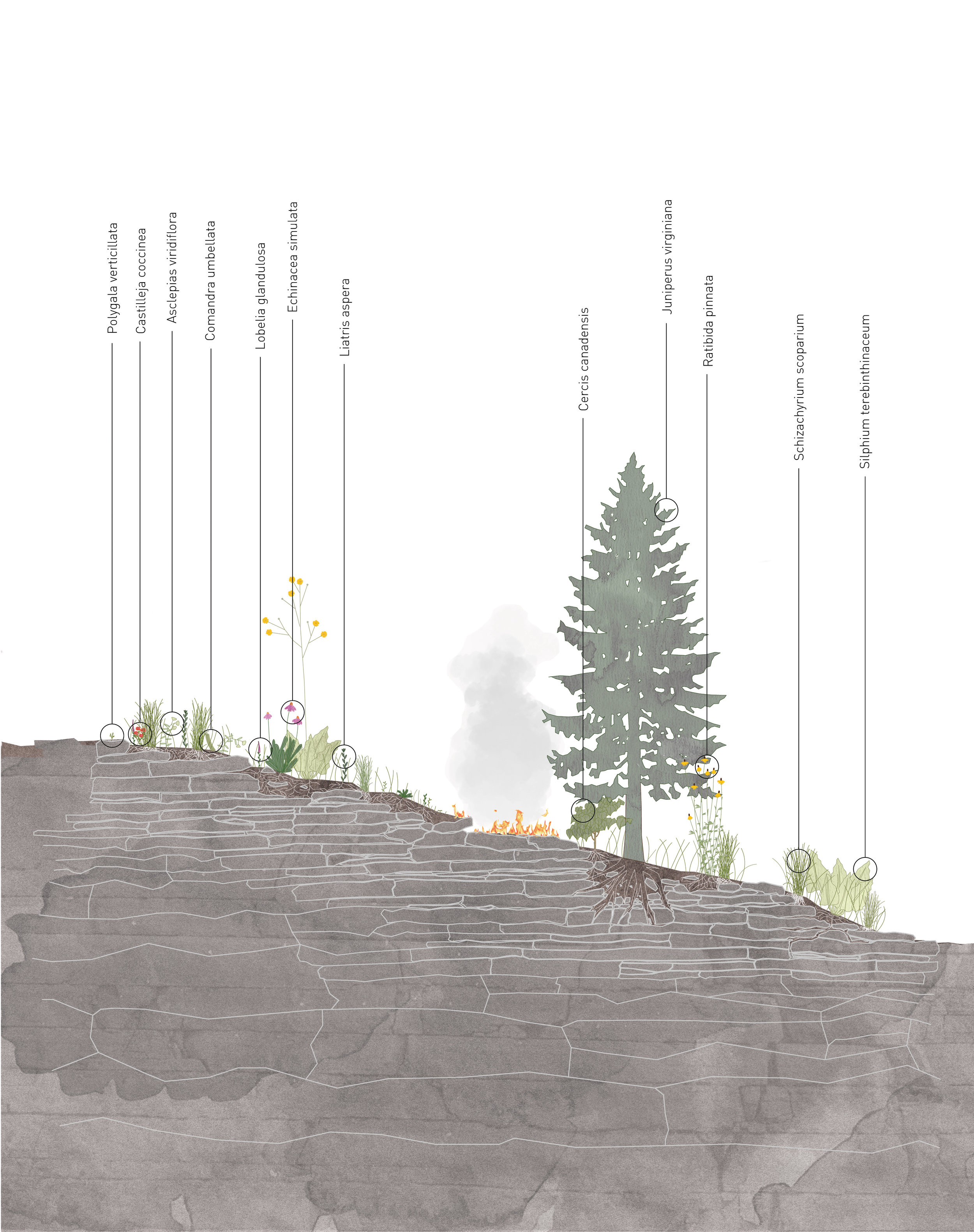

Through our own review of ecology research, we have learned about how industrial agriculture and (sub)urban development have supplanted soil conditions that once supported tallgrass prairie and Ozark woodlands. Today, we dwell on paved ground, in an assemblage of urban heat islands. We have streets, buildings, plazas, and parking lots. We have learned, though, that Missouri also has a drought- and heat-tolerant ecosystem—the limestone/dolomite glade. Produced 8000 years ago in a hotter and drier North America, this ecosystem is a part of our legacy. But is it our future?

We are proposing an artistic space to demonstrate the brilliance of these climate-resilient plants. We also wish to support urban ecological research through the design. An Environmental Learning Garden will offer St. Louis residents a vantage point to discover local ecology, through time. The installation is both a scientific experiment as well as educational exhibition, that we hope could raise awareness about our environment.

The research will take place in plots, separated by the public by elevation. The plots will be plinths. Nested into each each raised plinth will be a container, where we will cultivate the glade plant community, treating each plot differently to test how little soil and how much drought this system can tolerate. The public can view the garden in one of two ways. One is to approach a plinth and observe the garden through a reflection in a security mirror above the garden, pointing down. The second way to view the garden plots is to move up the ramp to get a higher ground on which to look down at the top of the plinths. The sides of the plinths and the ground will carry arresting graphics, drawing people into the garden. Every surface of the installation will tell a story, share knowledge, ask questions, and incite dialogue.

Jacob Longmeyer’s drawings—visualizing the glade’s soil depth, plant community, root growth, and the ecosystem’s stability (if fire-managed) or succession without human management.

Brooke Bulmash’s drawing is a map of elevation, parks, vacancy, and other kinds of open space. We are looking for a very public and transit-accessible site which is high, dry land, with solar radiation (no shadows)

Brooke Bulmash’s shadow studies of Downtown and Cortex neighborhoods in St. Louis show where there is enough solar radiation for our plant community to thrive.

A minimal environmental learning garden

Our proposal for the Cortex neighborhood (in central St. Louis) would be sited just off the Metrolink light rail station. One of the primary features are the raised research plots—’research plinths’— which elevate and therefore protect the ecological research away from spectators. On the side of the plinths are exhibition materials that visualize our regional ecosystem history as well as datagraphics and predictions for the future. Each research plinth has a security mirror to reflect the goings-on in the garden back to the spectator. The (red) accessible ramp also raises spectators to see the top of the research garden. Short plots (also green) are for demonstrating how to make a glade garden in a sunny spot in your property or on your roof. The other short boxes (in pink) are benches for contemplation. This research garden tests different soil substrates—crushed limestone and concrete, which are ubiquitous in St. Louis. This ‘minimal’ garden would serve as a proof of concept, testing our implementation ideas, as well as helping us tune aspects of our larger research agenda.

A full environmental learning garden with replicates for better research

The proposal for Downtown St. Louis is similar to the ‘minimal’ garden above, but this garden is also scaled to serve as a ‘mesocosm experiment.’ In ecology, the mesocosm experiment in an intermediate between two traditional research scales: on the smaller side are controlled labs and greenhouses; on the the larger side are field plots. In a mesocosm experiment researchers study interactions among multiple lifeforms and environmental conditions at once. The medium scale still builds in constraints to learn about underlying mechanisms of observed ecological phenomena. These are outside, most often in the elements and therefore approach functioning ecosystems.

Our mesocosm, “An environmental learning garden,” will help us to learn more about whether the plant community in this ecosystem is preadapted for harsh urban conditions. At the same time, we want the garden to show off the amazing history and value of this dwindling regional ecosystem to a larger public. Though threatened compared to pre-settlement documentation, we think the plant community in this ecosystem might also have the right adaptation to degraded urban conditions and for the future climate predicted of St. Louis.

This new perspective depicts the Learning Garden on Washington University in St. Louis, next to the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts. This view also shows various ways people can engage the garden. The ‘research plinths’ discourage meddling with the ecological research, though the security mirrors fixed to the raised beds show viewers what is going on in the plots. The lower ‘demonstration gardens’ encourage people to touch, smell, and get close to see the tested plant community. Benches also make the research garden a contemplative place.