Public Space & Ecological Knowledge

—an elective seminar in landscape architecture

Washington University in St. Louis

Fall 2020

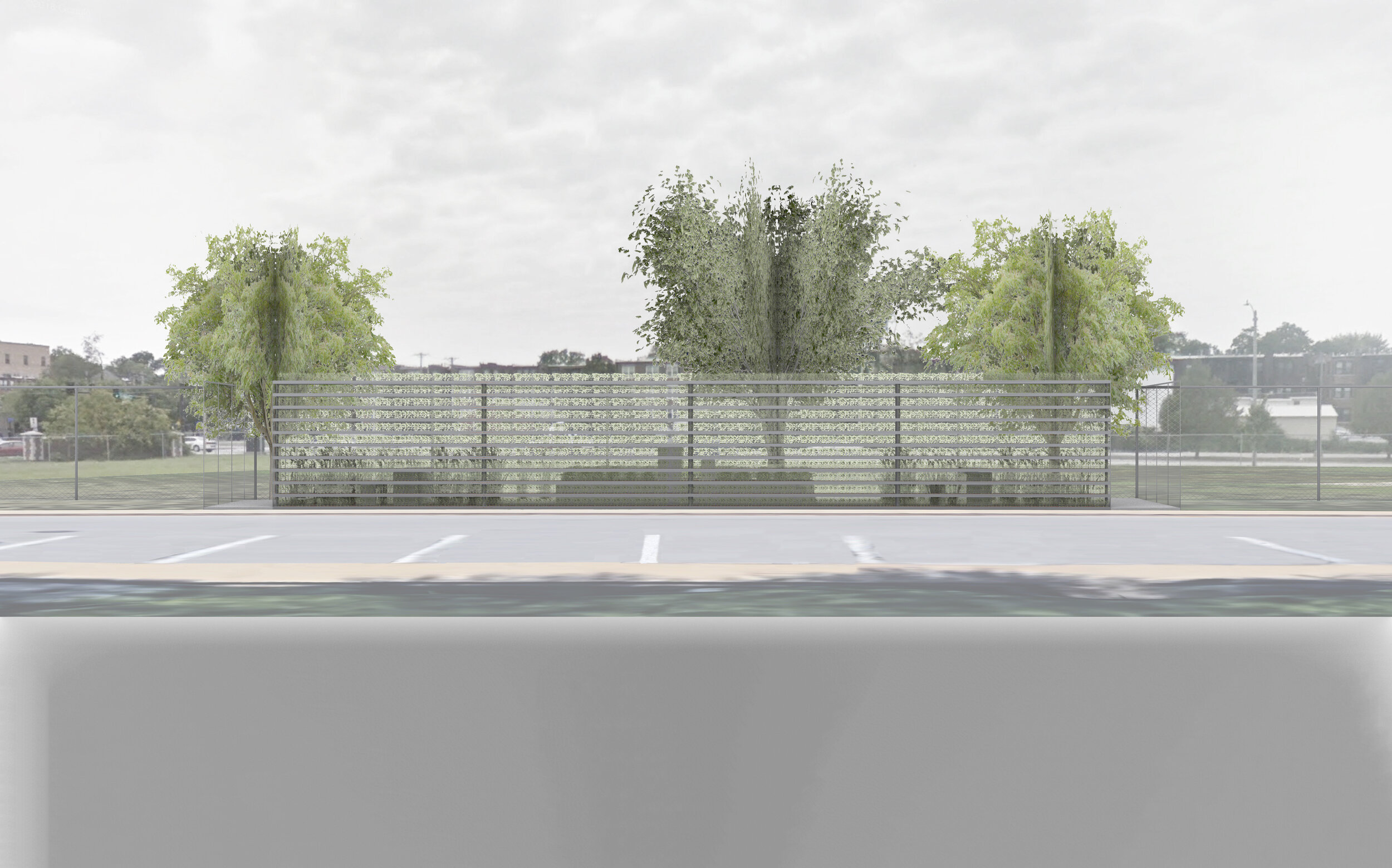

A view of John Whitaker’s final proposal.

Public space is shaped by design but also by political, social, and environmental dynamics. Ecological design, especially on public land, requires alignment of various values, desires, and systems. One factor that limits the cultivation of a more ecological urbanism is the knowledge gap about urban ecological systems. Urban ecology research is on the rise, but experiments sometimes come into tension with the public. This course located excellent examples of ecological design from history to the present, discusses the role of the advocacy and public awareness, and speculates about how design could further collaborate with ecology.

The first half of the semester was spent reading, touring—in person or virtually—conversing with experts, and researching as a group. The second half of the semester was spent studying a single public space to understand how ecological ideas are studied there and how ecological values are cultivated through design and operations. This course asked the following questions. Should ecological agendas be a matter of science and governance, or does ecological urbanism require democratic participation? Can designed spaces communicate ecological ideas for a larger public? Could design even be instrumental in the discovery of new ecological ideas? Toward the end of the semester, the students made speculative design, but in preparation of a 1:1 project. Markers, signs, or some other systems of interpretation will hopefully be staged on Washington University in St. Louis campus or in Forest Park, in an attempt to draw residents into ecological discourse.

The Index

An index of concepts for amplifying ecological knowledge in public space, by John Whitaker.

An index of concepts for highlighting ecological value in public space, by Danni Hu.

An index of carbon sequestration strategies for testing and raising awareness in public space, by Chuchu Qi.

The course began with 3 weeks of reading, lecture, and discussion on public space, publicness, ecology, epistemology, and intersections. Then, the students developed a matrix of diagrammatic drawings of examples of spaces where public space and ecological knowledge might meet. Each student voiced their own intersectional interests and developed their index. This drawing helped students transition from literature review to project framework.

The Tours

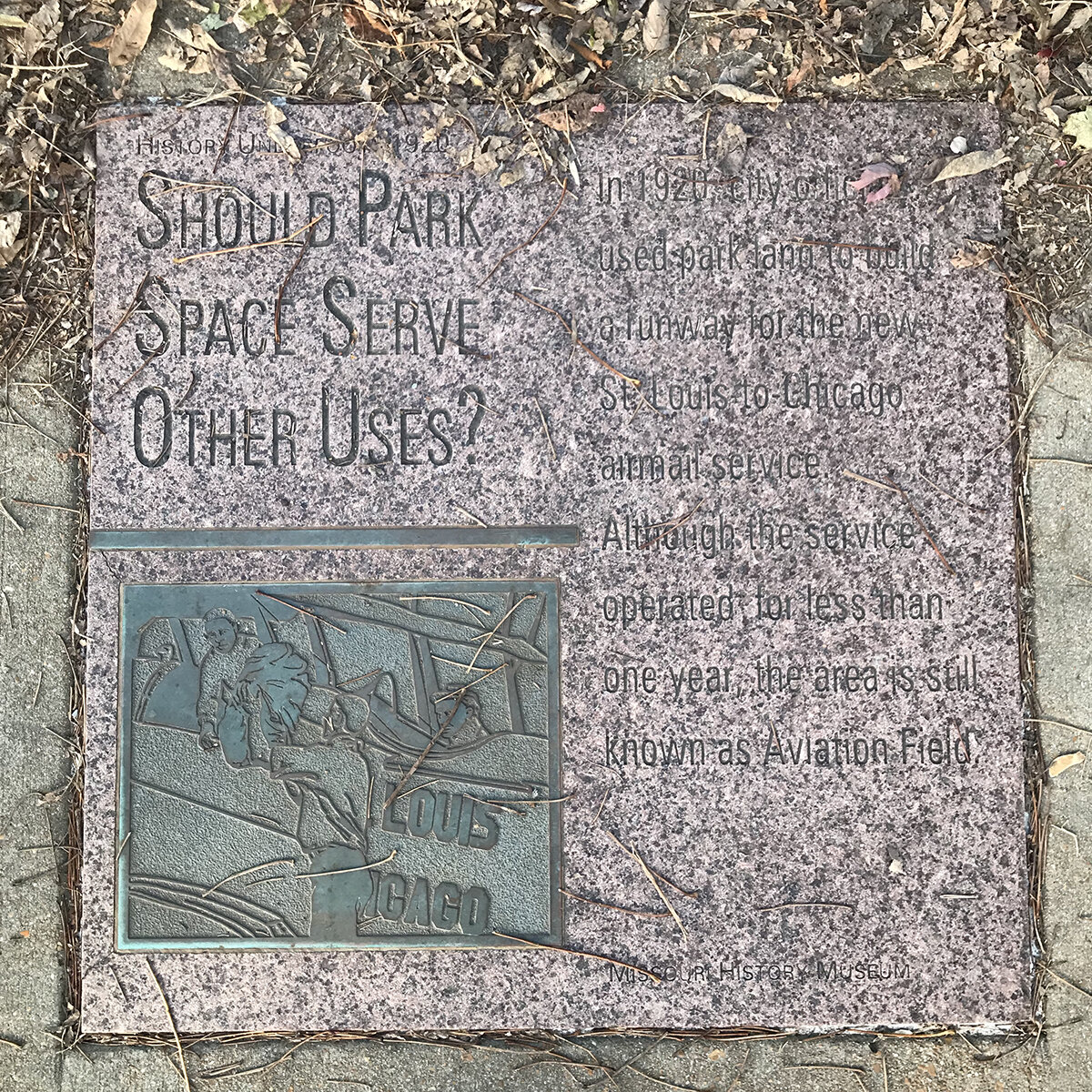

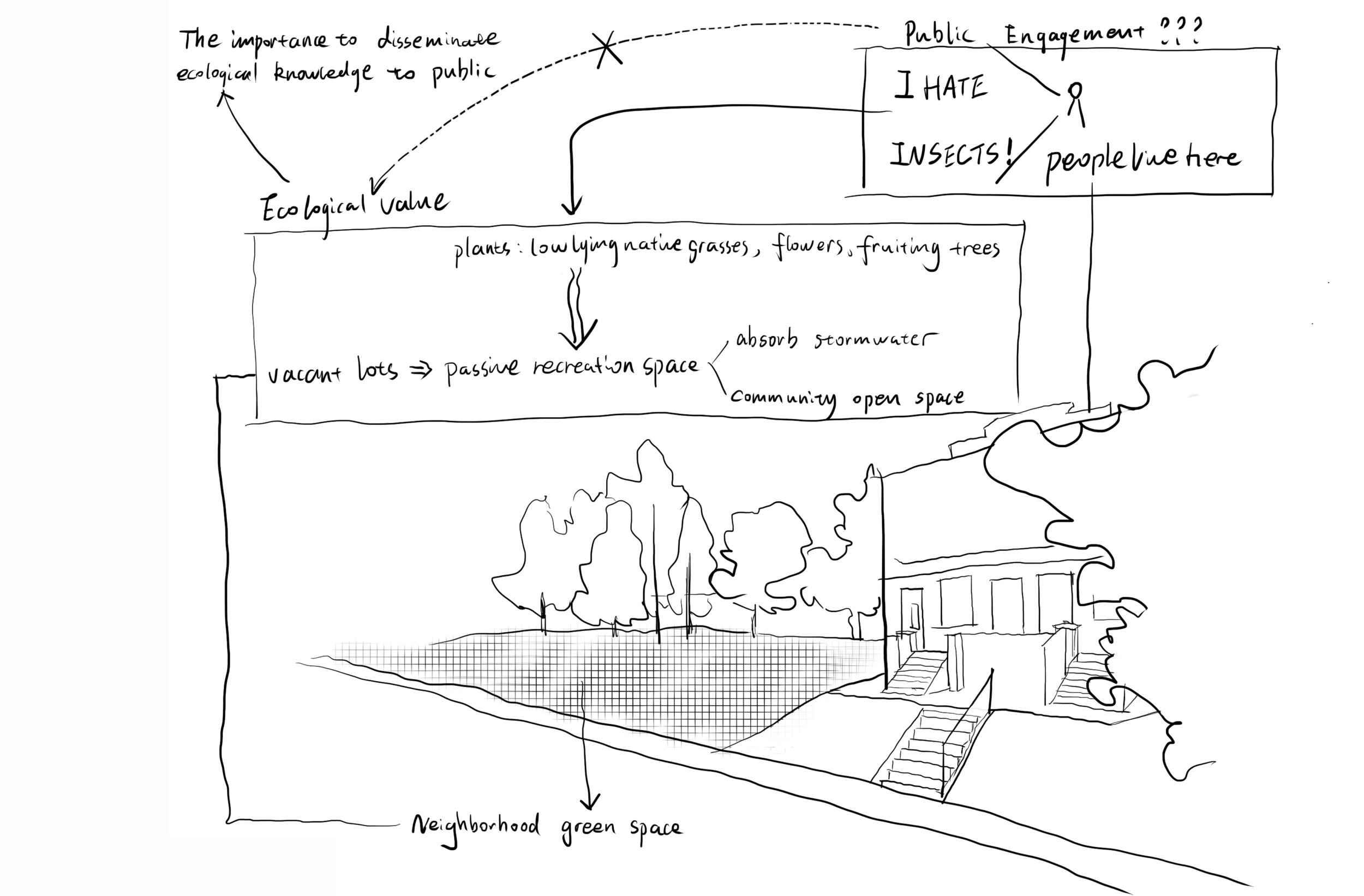

Next we took 2 hybrid (in-person and virtual) tours through Forest Park and Washington University in St. Louis campus. We toured solo in the park and on campus our tour guide was Cassie Hage, Assistant Director of the Office of Sustainability. We looked at park and campus spaces, looking closely the ways various publics read ecological design. Some spaces are curated and some are not, but we began to locate interpretive devices and pondered other ways publics might tune into ecological ideas around us. We also spent a virtual class period with Laura Ginn, Vacancy Strategist for the City of St. Louis and Green City Coalition.

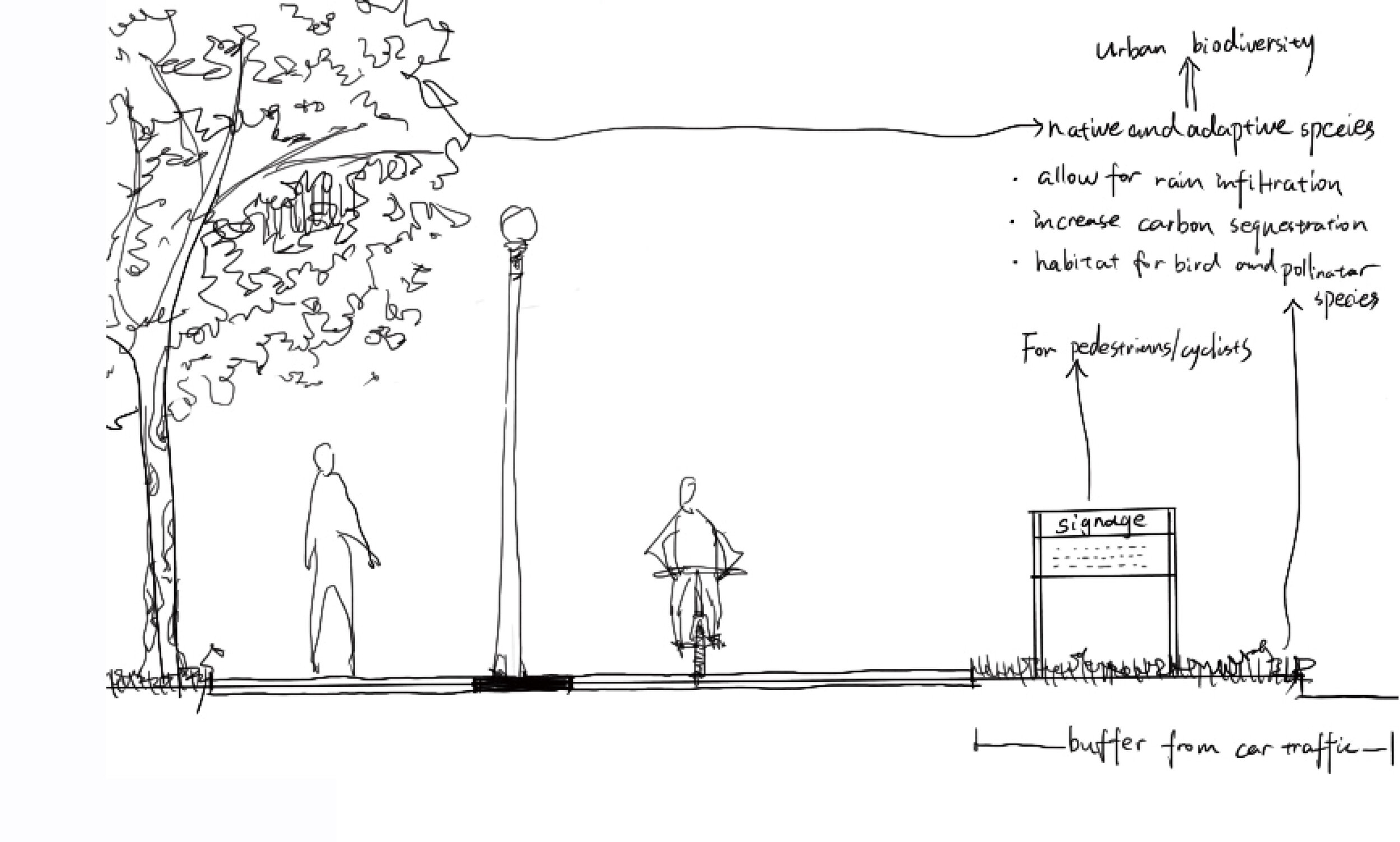

Students produced sketches for each ‘tour’ day to home in on their ecological interests and how public spaces communicate intent or value.

Designing for Public Space & Ecological Knowledge

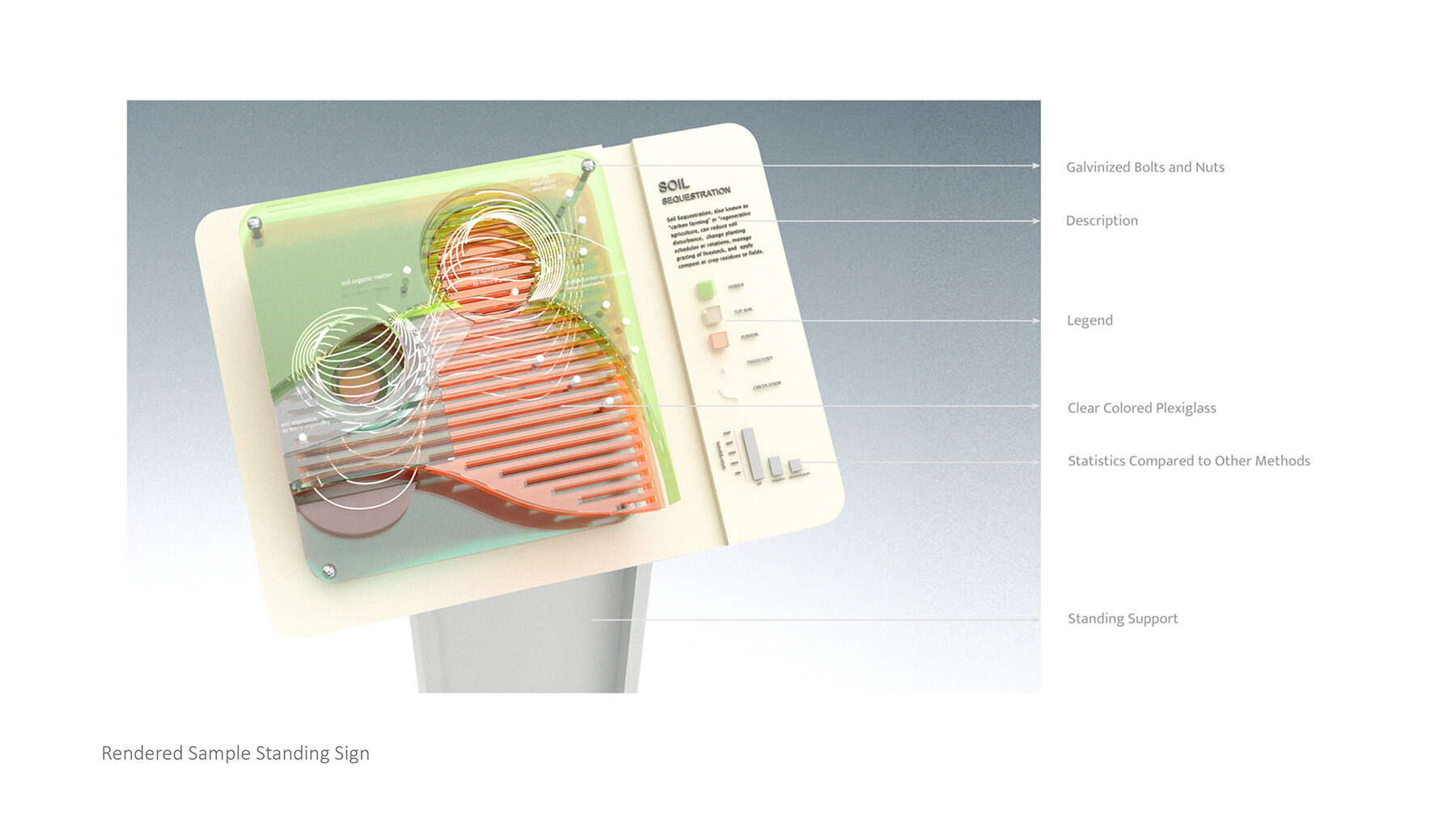

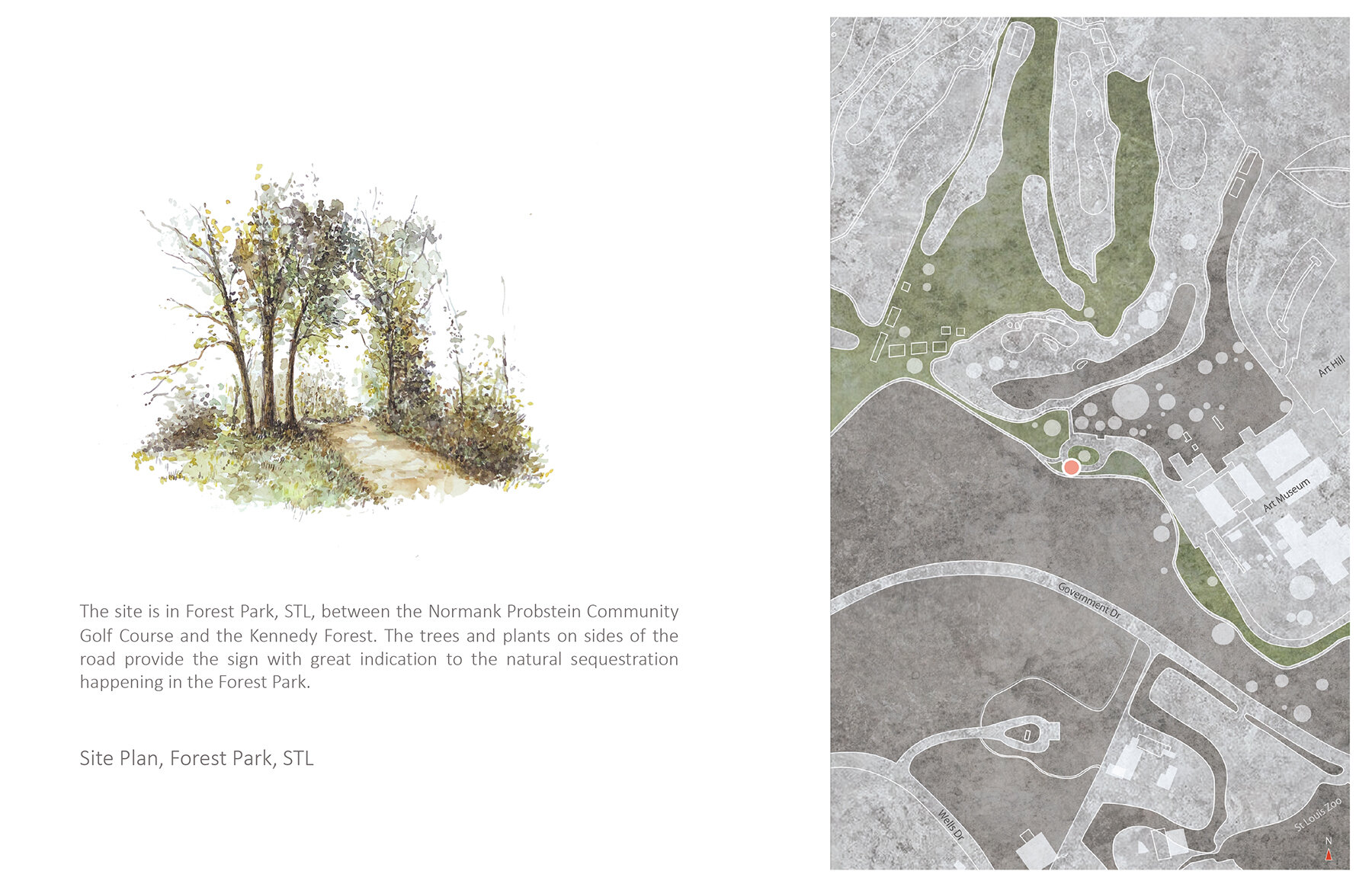

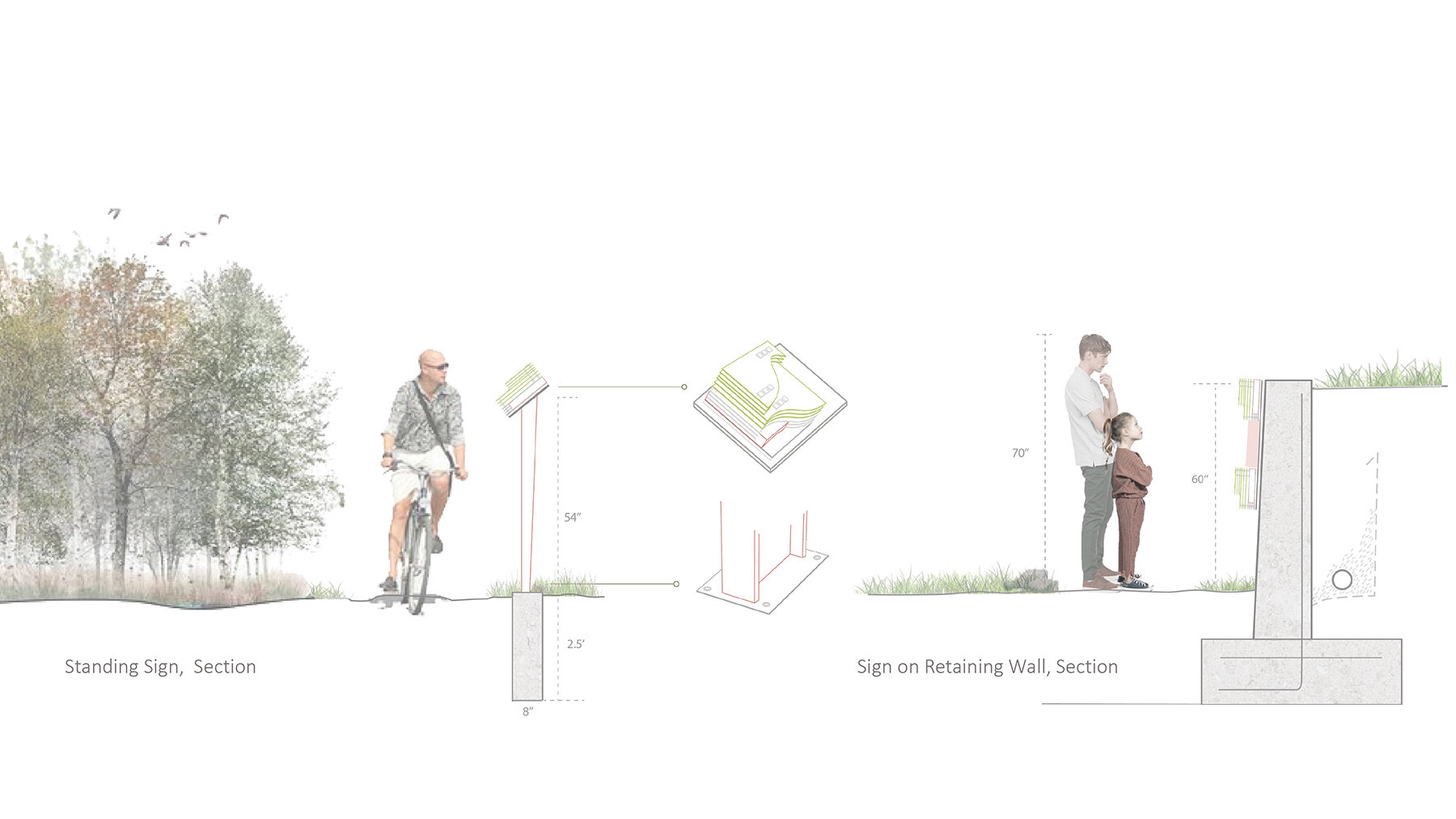

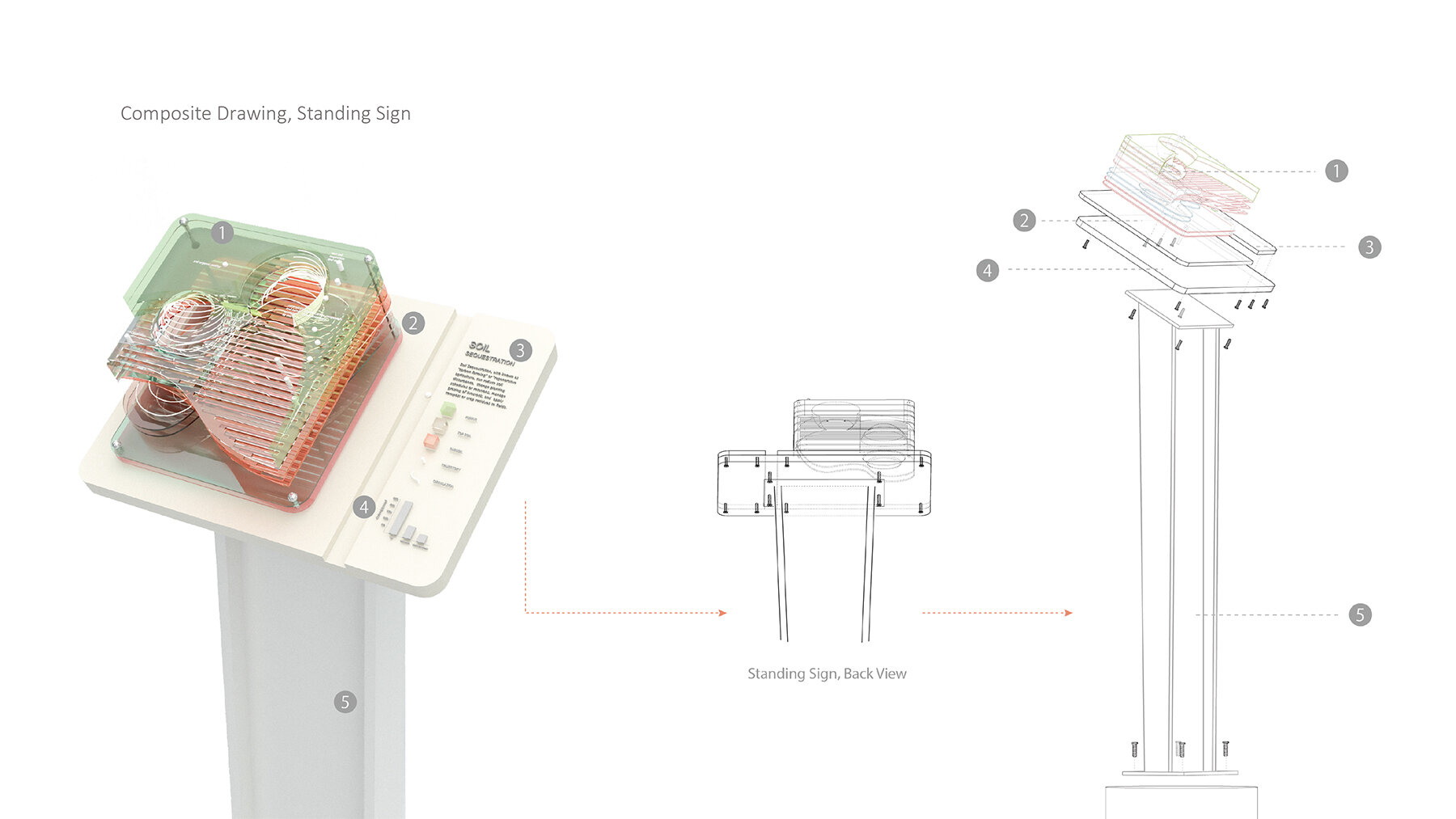

Chuchu Qi’s project curates existing carbon sequestration strategies found in Forest Park, while also suggesting new strategies. The signs highlight and compare living and non-living carbon sequestration systems. Those not in the know can be introduced to carbon’s importance and learn how we can wield it.

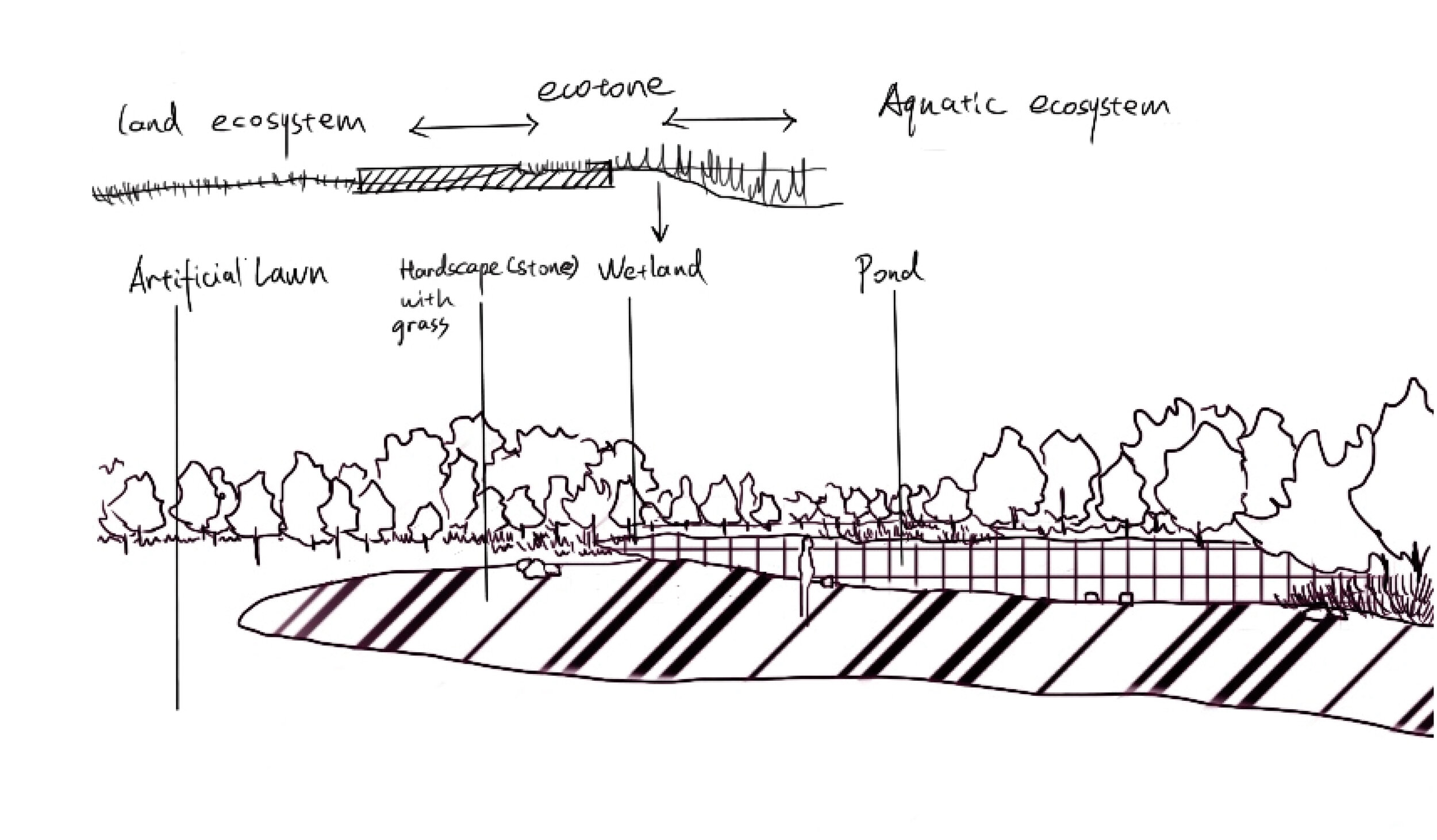

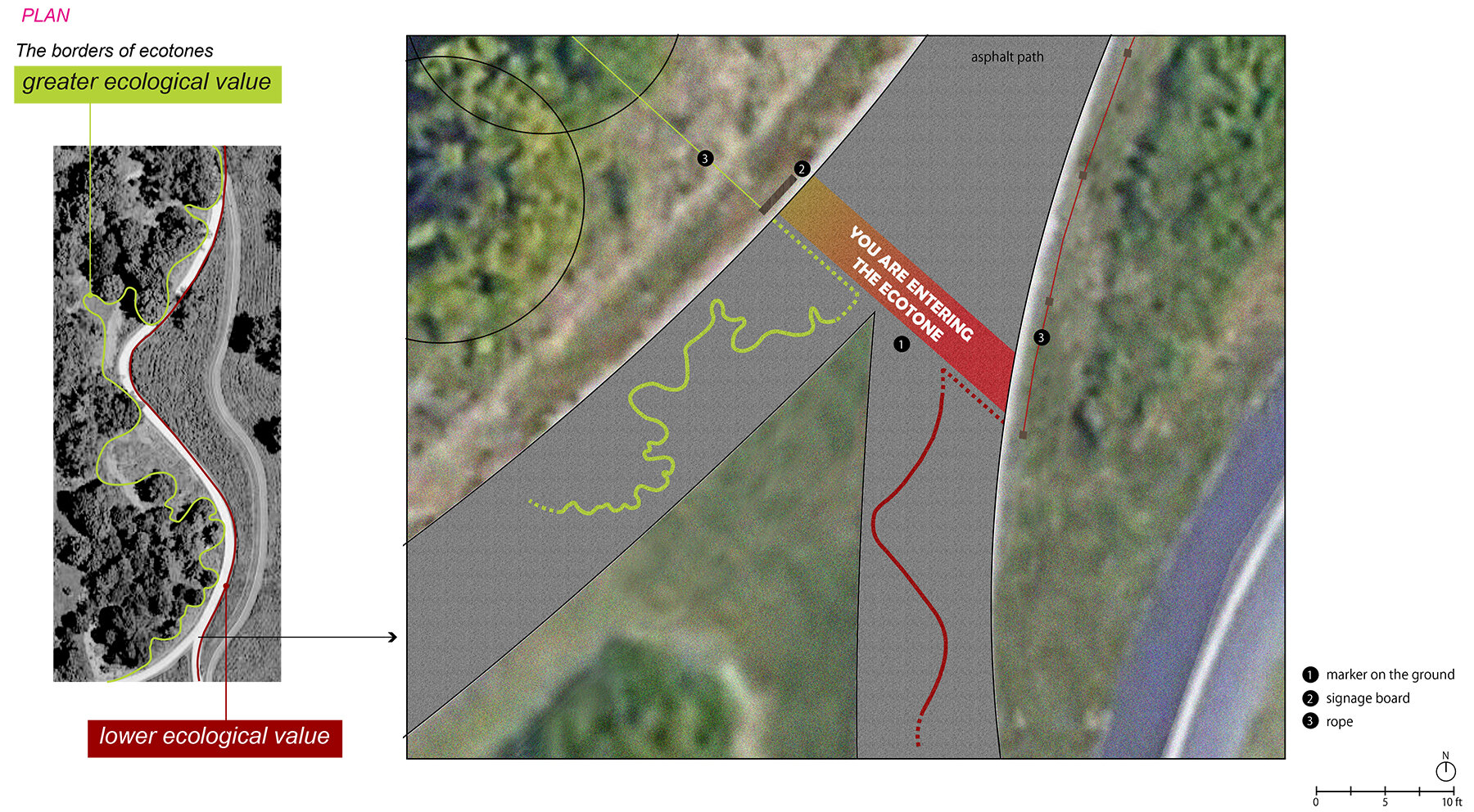

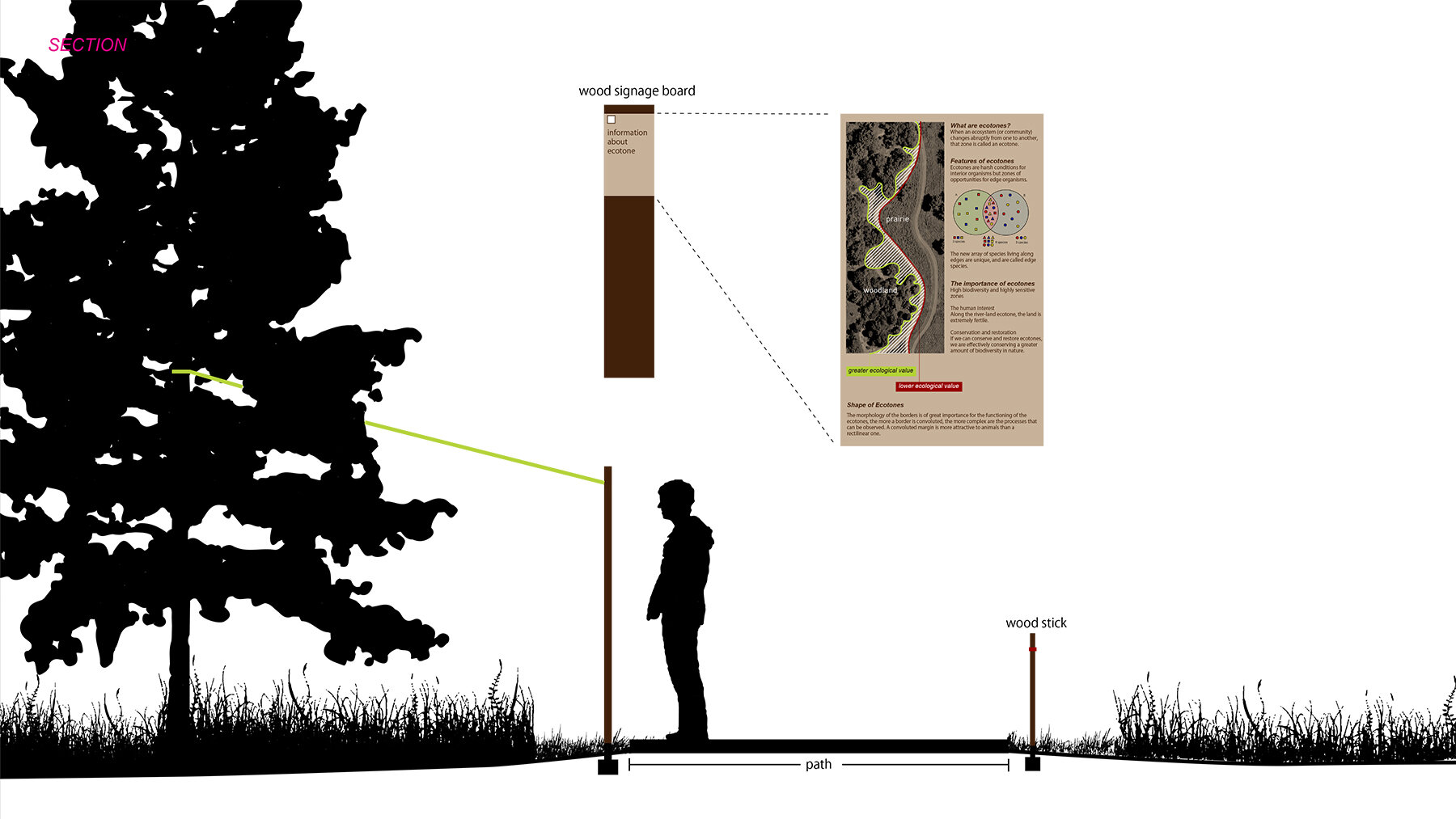

Danni Hu’s project curates ecotones in Forest Park, where ecological restoration efforts have yielded diverse native systems that used to dominate Missouri—the oak-hickory woodland, the oak savanna, the prairie, among others. On a path that cuts through the savanna and prairie ecotones, her interpretive material interrupts passers-by with arresting graphics on the ground as well as markers and signs off the ground. This project offers am interpretation system in an ecologically valuable part of St. Louis City, since there is little signage now.

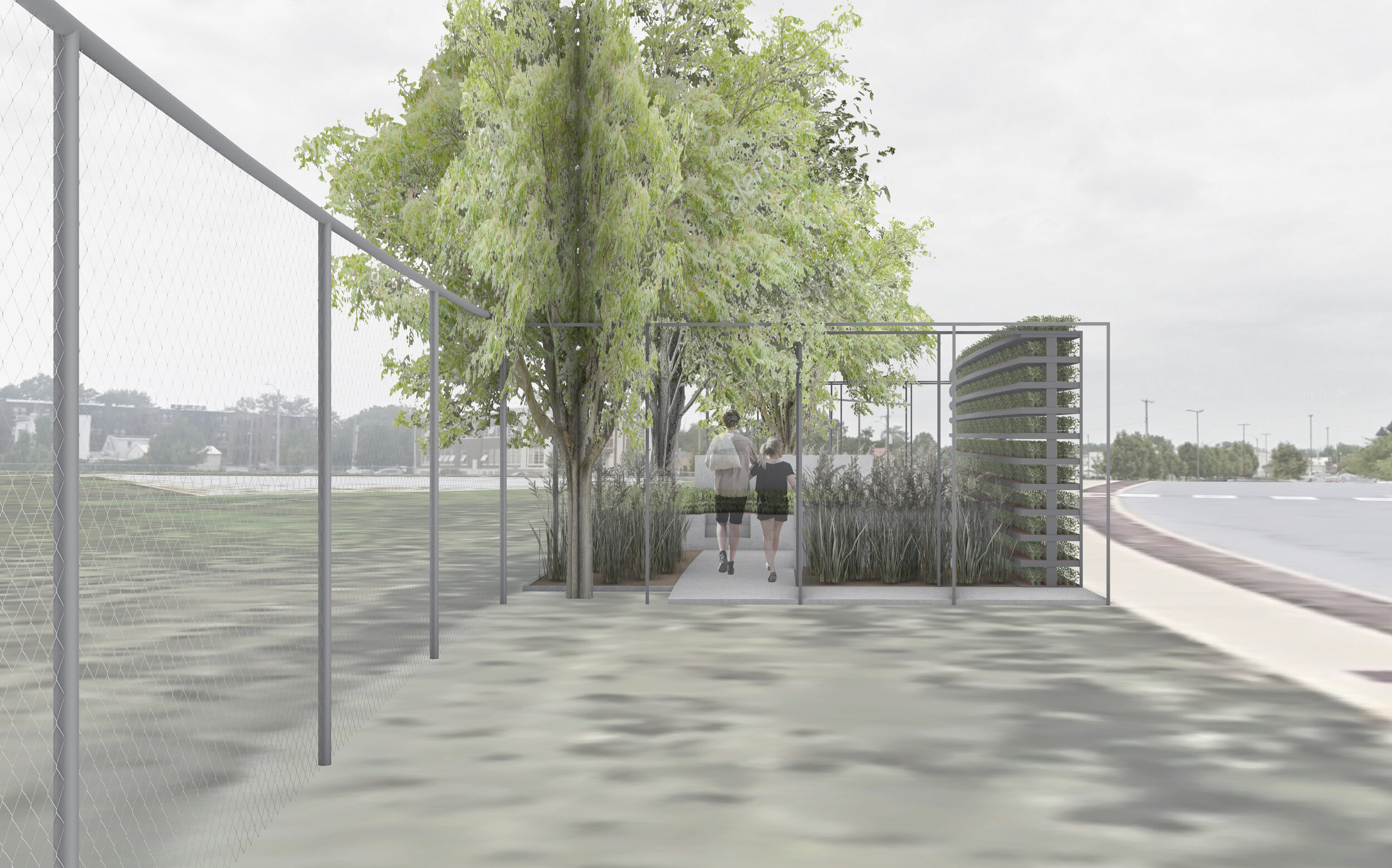

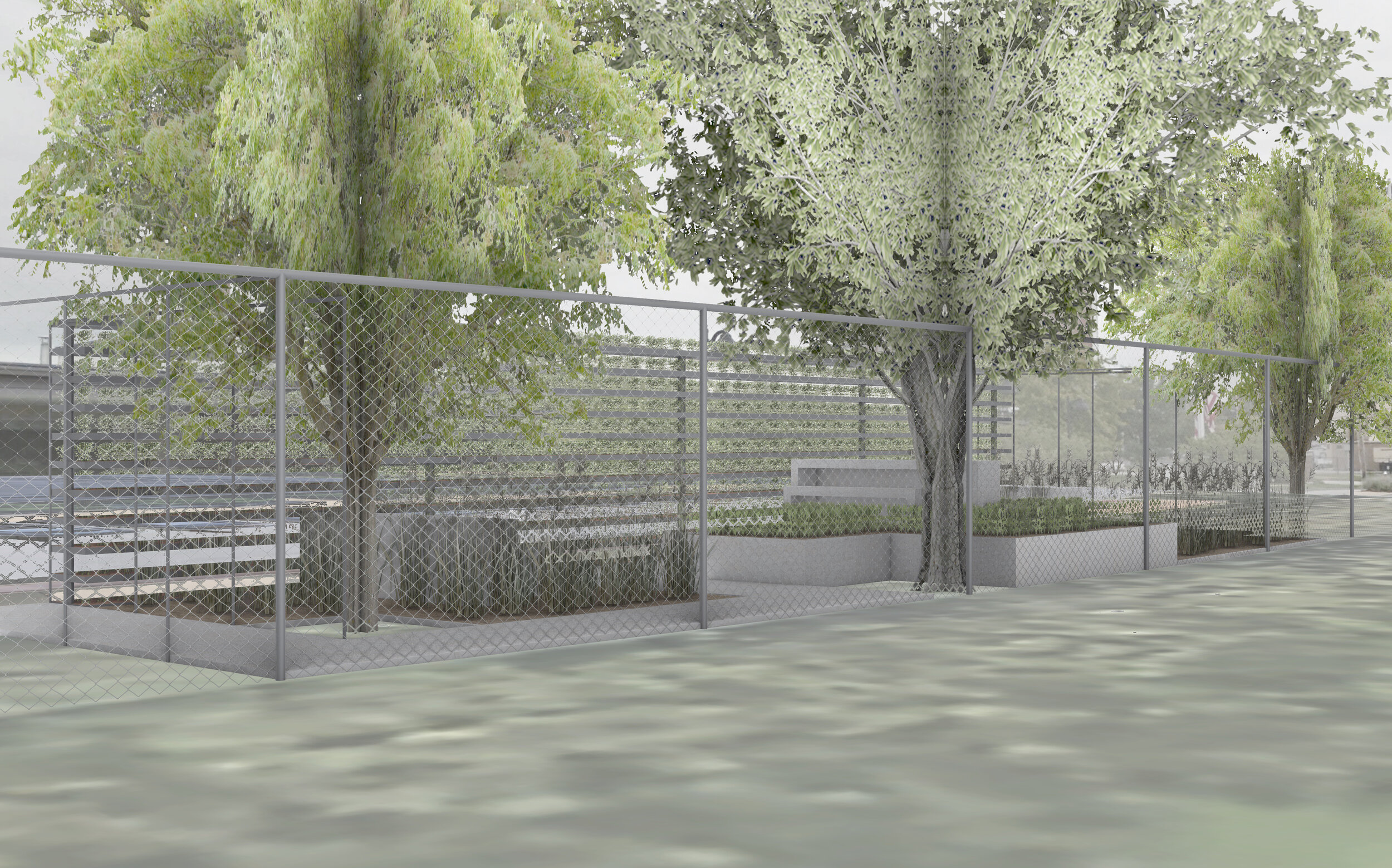

Boyan Zhang’s project takes interest in the plants that are preadapted for human-made, urban spaces. Inspired by Peter Del Tredici’s article, “The Flora of the Future,” this small garden is a simple expansion of a typical run of chain link fence. Purslane is adapted for moisture hiding in sidewalk cracks. Phragmites can absorb excess nitrogen found in contaminated sites. Artemisia can adapt to salty soil, found on roadsides due to the tradition of salting roads in winter. Ailanthus is adapted to grow along fence lines. In certain tough environments, some plant life thrives. Boyan’s garden celebrates the emergence of these weedy, wild urban spaces. If organized in a deliberate garden, can these often unwanted plants be appreciated?

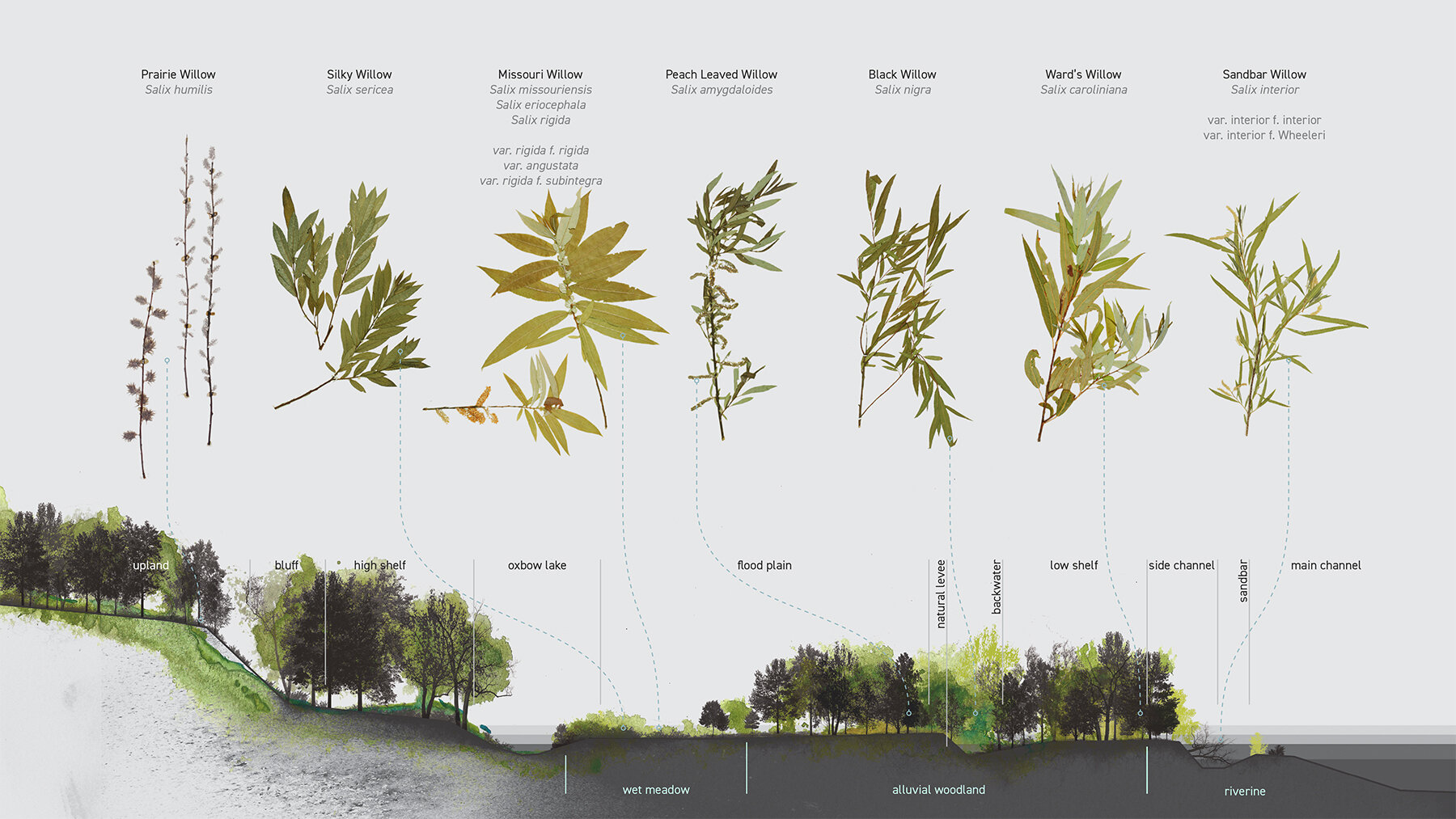

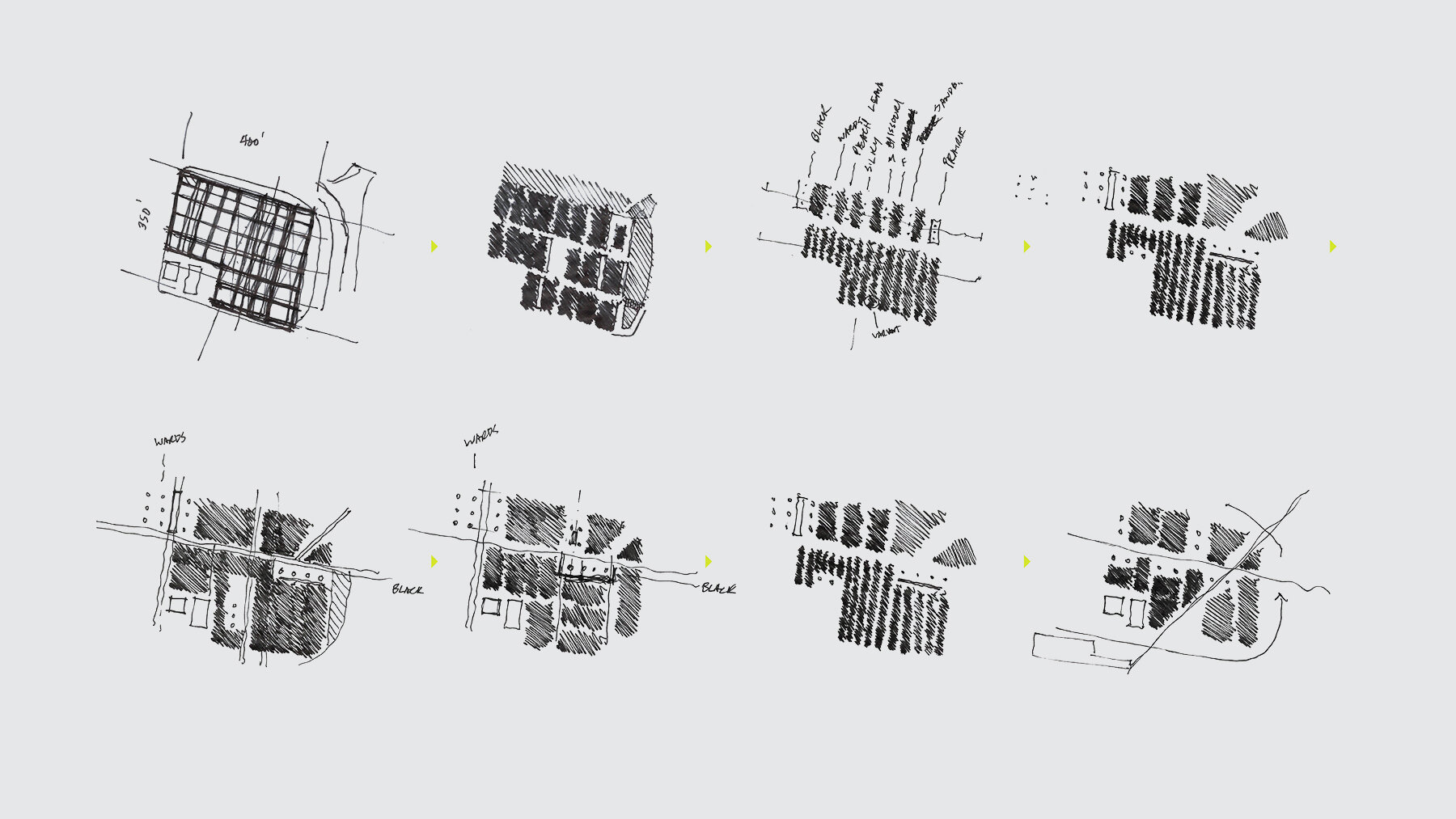

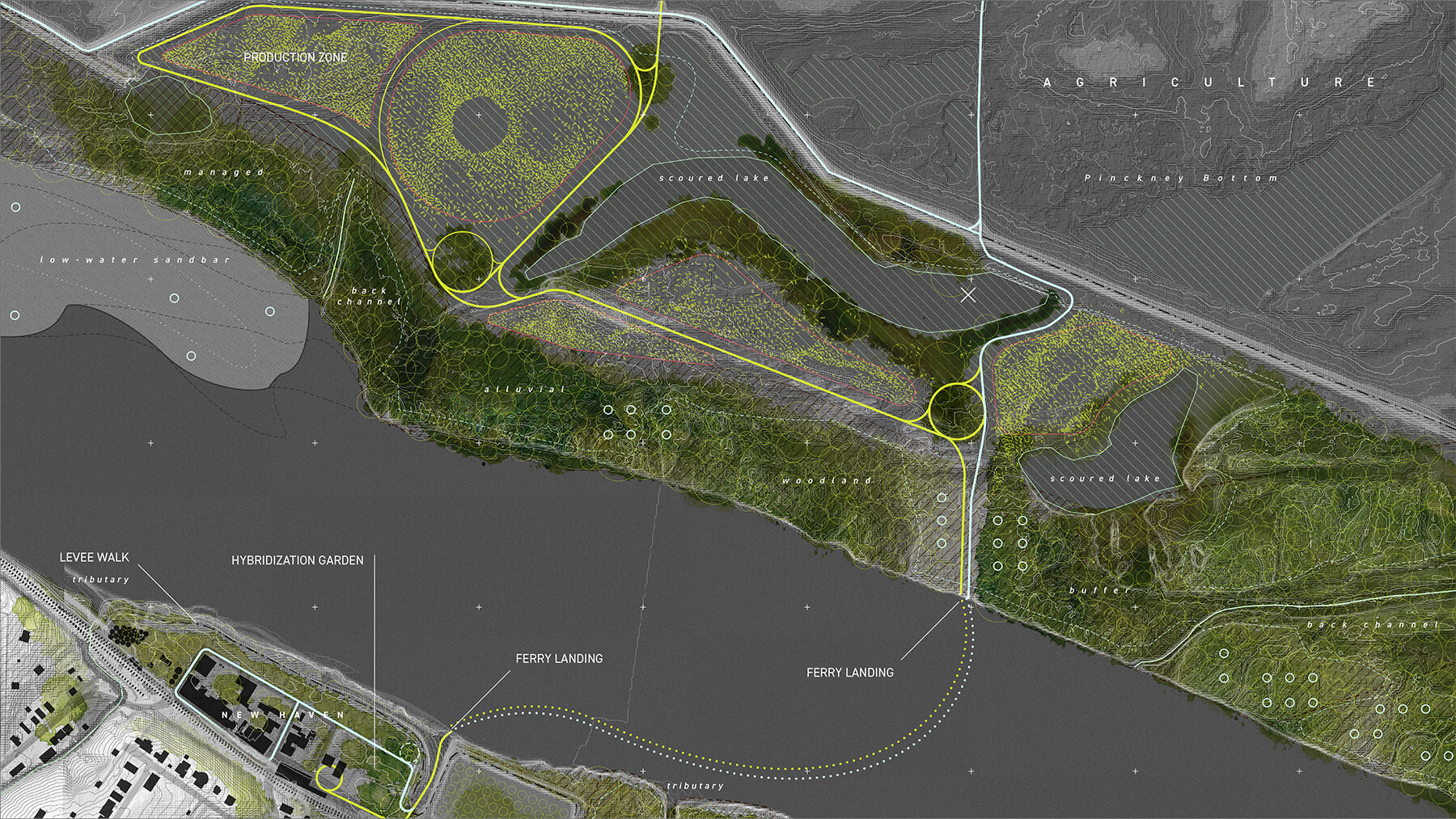

John Whitaker’s project builds on a studio project developed a few semesters ago, with Rod Barnett. In the Missouri River Valley outside of the St. Louis region, agriculture dominates and the river is managed with levees for agricultural production. John’s project identifies a floodplain plant whose genus has rampant hybridization, which needs further study. The site project suggests a mesocosm garden for controlling and measuring the various willow species selected, and at a larger scale a biochar fertilizer production enterprise. The project takes place in the floodplain, where areas unprotected by levee have little economic value but a bounty of ecological value. John’s project aims to work with, highlight, and increase both.