Confluences: St. Louis & its Hinterlands

—advanced studio in the 3nd year of the MLA program

Washington University in St. Louis

Fall 2021

Semester-long special guest reviewer: Chip Crawford, FASLA, PLA, LEED GREEN ASSOCIATE | Planning & Landscape Market Leader | Managing Director at LJC

Heyue Liu’s project at the end of the infamous Bubbly Creek suggests that wetland restoration can contribute to cleaning up the toxic legacies in this part of the Chicago River, as well as perform carbon sequestration. To manage the drier parts of the site, where wetland transitions to wet prairie and drier prairie planting, she suggests that a regime of prescribed fire is best to manage this sight to increase native biodiversity. The fire releases carbon into the atmosphere, but keeping ecosystems healthy is always a trade-off.

The Syllabus

The Chicago Drainage Canal connects the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence River, and the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River Watershed, St. Louis, and the Gulf of Mexico. The short distance between two watersheds and subtle topography made it possible to reverse the Chicago River and control water levels. In recent years, though, climate change has caused dramatic swings between drought and flooding in this area. The south fork of the Chicago River and the origin of the Canal is also surrounded by diverse neighborhoods, where low-income Chicagoans bear the brunt of flooding but also legacy toxicity and contemporary pollution.

How can we change environments vastly better? And by better, I mean a lot more sustainably but also a hell of a lot more equitably.

—Jenny Price, Stop Saving the Planet: An Environmentalist Manifesto (10)

As a response to climate change, landscape toxicity, and social inequity, many landscape architects have turned to lenses or developed lenses like reclamation, remediation, sustainability, ecological design, environmental justice, resilience, and climate positive design. To avoid ‘greenwashing’—where we prioritize optics over meaningful transformational practice—we need a great deal of knowledge. Without critical acuity, we assume heroic ‘save the planet’ stances. If we want meaningful impacts, landscape architectural practice ought to be more specific and nuanced with our words, our drawings, and our propositions. How precisely can landscape architecture contribute to the slowing of the global warming and the other wicked effects of climate change? Who are our best allies in these pursuits?

To take a few steps back, we might ask if landscape architecture is so well positioned to deal with the greatest environmental crises we face today. Has landscape architecture dealt with its own relationship to extraction, pollution, and waste?

In order to adapt and innovate landscape architecture practice, we must understand where we are now and how we arrived here. Thus, this advanced Master of Landscape Architecture studio will engaged a practice partner—Chip Crawford, Managing Director at LJC. This collaboration gave the studio a window into allied professionals, a breadth of global landscape architecture and planning experience, and a strong connection to the City of Chicago. LJC is located in St. Louis and Chicago.

This studio allowed students to make their own theses about Chicago, landscape architecture, and climate change, starting with the following prompt:

As a team, the studio maps Chicago’s history—from geology to indigenous people’s history,

to European colonization and the development of the modern metropolis.As a team, the studio maps contemporary environmental situations—droughts, floods, pollution, and social inequity. How does climate change relate to these situations?

Keeping consistent studio graphics, students will—individually—study contemporary projects and measure landscape architecture practice against wicked problems. Precedents: Chicago Riverwalk, Palmisano Park, Millenium Park, Lurie Garden, Maggie Daley Park, The 606.

[Teamwork ends]

Utilizing the teamwork, students analyze history and begin telling a story about how Chicago

ought to plan for the future. Students will work around the South Fork of the Chicago River.Students argue for a particular site where they can explore a design research question.

Students set aims based on the wicked problems and their criticisms of contemporary practice. Students make climate positive designs. They manage water for drought and flood contingencies. These projects reuse materials, deal with toxic legacies, and add value to vulnerable or marginalized neighborhoods. These landscapes speak to power.

Mapping Histories

Research conducted and compiled by Zhiyi Feng, Sweeta Jura, Heyue Liu, Jonathan Myers, Jennifer Wang, and Shuya Zhang

The students, as a team, studied Chicago’s geological, ecological, and cultural history, including its rapid growth into an industrial city. Chicago’s unique geology, shaped by glaciation, made it quite easy to navigate between two watersheds—the Great Lakes basin and the Mississippi River Basin (via the Illinois River). The post glacial landscape left swamps and moraines that rise up maximally to 100 feet above the average lake level. Much of Chicago is just above the lake elevation, making it a wet landscape, which slow moving water. Ecosystems found in Chicago before colonization were tallgrass prairie, oak savanna, open woodland, and wetlands that included wetter expressions of many of the upland ecosystems.

Indigenous people, who are credited to introduce fire as a tool to manage prairies and woodlands, further shaped the ecology. Indigenous people settled the Chicago area thousands of years ago. When Europeans came to this area, they found Indigenous people living on ridges and utilizing a complex network of waterways for hunting, gathering, and seasonal migration. The word Chicago comes from the Miami-Illinois language for wild onion, shikaakwa, because the confluence of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan was an abundant place for harvesting this plant.

European colonizers took advantage of this rich ecology and known waterways to easily trade. After extracting furs and other materials desired in Europe, the easy connection between watersheds became an easy way to move other goods as well as people as more Europeans flooded into this landscape. The I&M cut an even easier route from the Chicago River to the Illinois River, helping the modern city of Chicago expand and industrialize. During this period the Chicago River was treated as a sewer and a dump. The river was so polluted, it eventually caused a number of problems (including the spread of cholera) to the drinking supply off the coast of Chicago, triggering the reversal of the Chicago River, so its effluent could be sent downriver into the Illinois River. That Shipping & Sanitation Canal is still part of the shipping and sewage management strategy today.

Mapping Contemporary Situations

Research conducted and compiled by Zhiyi Feng, Sweeta Jura, Heyue Liu, Jonathan Myers, Jennifer Wang, and Shuya Zhang

The students studied transportation and contemporary carbon emissions, policy and planning, toxic legacies in the land and waterways, recent floods and droughts, social inequity, and the state of the urban ecology. As a studio, we had many discussions about social equity in the context of pollution, urban redevelopment, and ecological management. This work supported our desire to look at the Chicago River and helped us to make an informed decision to work on the confluence of the Chicago River and the S&S Canal. The students worked as a team, but each produced one map of personal interest, which helped them to think deeply about the past and contemporary situations so they could make their own arguments and argue for their work in the next phases of the project.

Planning Futures

Research conducted and compiled by Zhiyi Feng, Sweeta Jura, Heyue Liu, Jonathan Myers, Jennifer Wang, and Shuya Zhang

Based on the students’ research about history and contemporary situations, they looked at the scale of four neighborhoods to further understand what is happening on the ground and to propose some planning scale design. This scale of work in the studio was meant to help the students to site landscape architecture in a neighborhood context that includes mobility, green open space, ecology, arts, and the telling of local history.

Individual Projects

Sweeta Jura’s project toys with a common landscape architecture strategy to make a larger, immersive playscape that also doubles as an environmental learning landscape. Her Project asks: how can I most efficiently design and maintain an industrial landscape, economically, environmentally, socially, and sustainably for a long timescale? The design answers this by planning an ecological playscape that meanders through a wet prairie, an open woodland, and even over a wetland. Additionally, the play with topography creates a moisture gradient to express more upland, mesic, and bottomland expressions f prairie and woodland. Sweeta’s design focuses on ecological restoration and her research shows that her project would only take six years to make up the carbon footprint, and to become carbon positive.

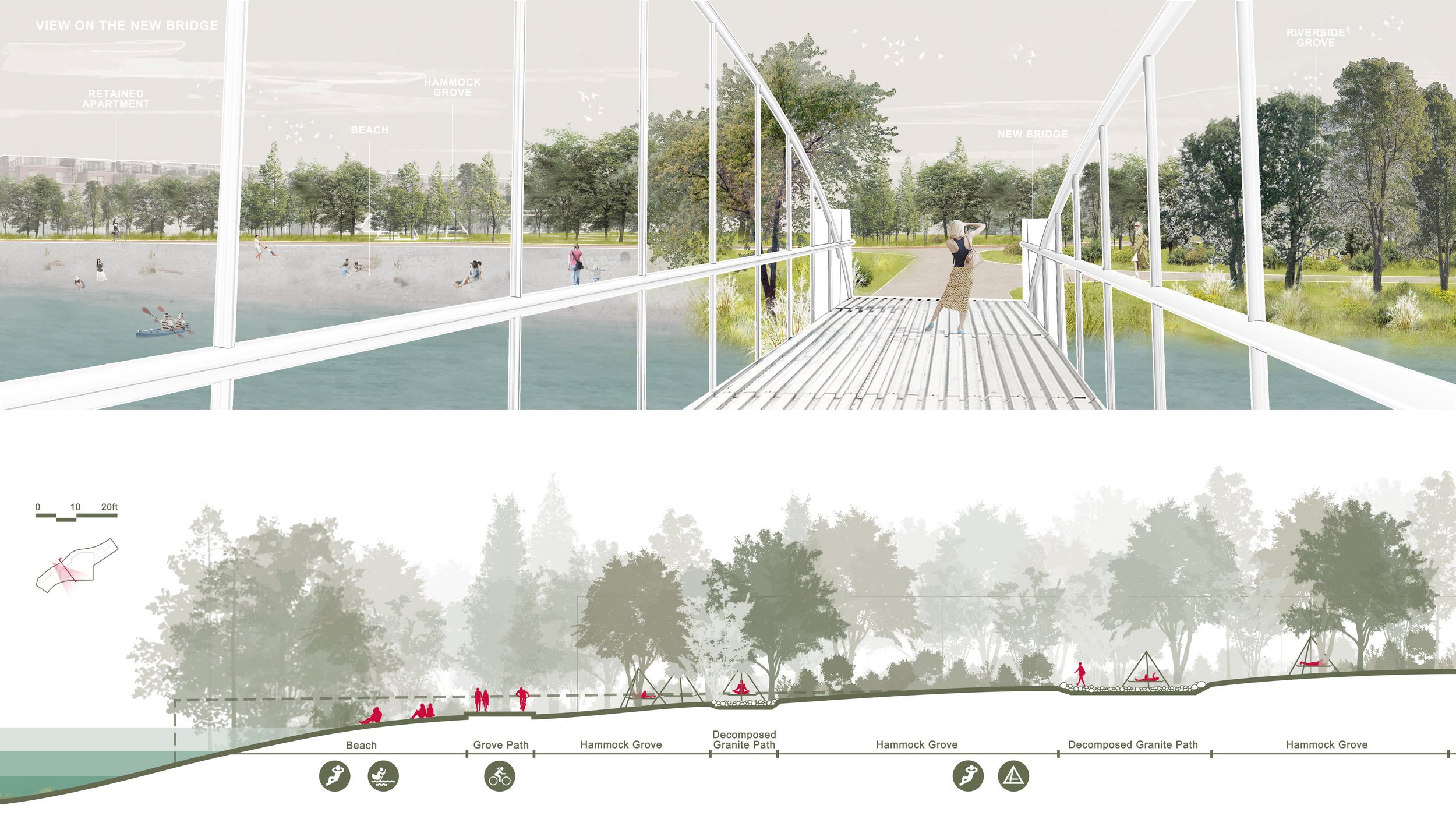

Shuya Zhang’s project is crafted by creating spaces and inviting people to experience landscape lifeways, which is inspired by indigenous memories in Chicago, which were either decimated or marginalized through colonization. The idea of the lifeway focuses on dwelling, foraging, and traveling. This site design is a process of recollection. Proposed programs and key functional areas are responses to these inspirations. Here we see the interaction between people and the landscape. The goal of this design is not to bring people back to the past, but to provide the possibility of dwelling within the landscape, in the urban environment, in ways that acknowledge the past. Also, the design considers some site issues and tries to improve resilience to floods, create shelter for homeless and provide opportunities to get close to Bubbly Creek.

The headwaters of Bubbly Creek, the South Fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River, has been plagued by floods and pollution problems for a long time. In recent years, the Chicago authorities have worked hard to clean up deteriorating sediments and improve the water quality, trying to restore the vitality of Bubbly Creek. However, Bubbly Creek is surrounded by industrial corridors that keep people separated from the waterway.

Heyue Liu’s project uses the rainy season floods to imitate the reverse of upstreaming the Chicago River, as the government reversed the Chicago River to ensure the purity of their drinking water in Lake Michigan. The imitated mechanism turns the water on the two parts of the site into a microcosm of history, echoing the river history museum transformed from an old factory on site. The project is also ambitiously committed to improving flood controls by adding a retention pond on the brownfield at the source. The renovated site connects the residential area to the new South Fork and Bubbly Creek, encouraging more public engagement.